Government and military projects are among the toughest challenges an engineer can face. Demanding facility owners, tight budget limitations, safety concerns, and other factors all come into play. Here, engineers with experience in the field offer advice on how to succeed.

Respondents

- Roger Chang, PE, LEED Fellow, Principal, DLR Group, Washington, D.C.

- Shem Heiple, PE, LEED AP, Associate Principal, Senior Mechanical Engineer, Interface Engineering, Portland, Ore.

- Dalrio Lewis, PE, Project Engineer, RTM Associates, Orlando, Fla.

- Spencer Morgenthau, CPSM, LEED AP, Director of Business Development, Southland Energy, a division of Southland Industries, Sterling, Va.

CSE: What’s the biggest trend you see today in government, state, municipal, federal, and military facilities?

Roger Chang: There is substantial interest in high-performance project delivery models, starting with the integration of design teams and construction teams as designer/builder entities, with significant emphasis on integrated sustainable-design solutions.

Shem Heiple: There has been an emphasis on high-performance building and sustainability. Legislative requirements have translated into building-performance standards specifically implemented for each government agency. High-performance design goals include minimum performance standards and performance stretch goals. Minimum performance standards include exceeding energy performance above ASHRAE 90.1: Energy Standard for Buildings Except Low-Rise Residential Buildings and stretch goals, such as meeting the 2030 Challenge (the goal for all new buildings, developments, and major renovations to be carbon-neutral by 2030). Emphasis is given on proving economic and operational viability of energy- and water-conservation strategies through lifecycle cost analysis.

Dalrio Lewis: We are starting to see a major trend in more energy-efficient or LEED-certified buildings with larger return on investments. Several municipalities are mandating by city or county ordinances that new buildings meet some form of energy accreditation.

Spencer Morgenthau: The biggest trend I see in today’s facilities is an increasing number of owners are reaching a breaking point with deferred maintenance. Since the economic downturn of 2008 and 2009, institutional facility owners have continued to underfund maintenance and infrastructure renewal as a means to balance shrinking facility budgets. We frequently encounter facilities with deferred maintenance backlogs that exceed $100/sq ft. Our clients report that continuing to put off maintenance, repairs, and replacement for key building systems has made emergency repairs, replacement, and the corresponding disruption of core business or mission a frequent if not daily occurrence.

CSE: What trends are on the horizon for such projects?

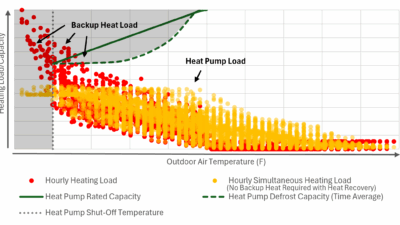

Morgenthau: Resiliency, efficiency, and distributed generation are converging to become the answer to the deferred-maintenance challenge. The financial case for replacing obsolete and failing infrastructure with today’s highly efficient systems will remain strong, and as we reach grid parity with onsite solar-, wind-, and biomass-generation solutions, net zero energy will become an added driver for facilities looking at the complete financial picture when budgeting renewals and modernization. As owners’ demand for facilities that can continue to operate without disruption from natural, cyber, or terrorist events increases, microgrid and energy-storage solutions are also reaching a tipping point.

Chang: There will be a continued focus on actual performance outcomes, where a team’s reward may be tied to first cost and used resources. This requires significant integration of shared knowledge between the owner, designers, and construction stakeholder groups.

Heiple: There is an increasing interest in achieving net zero energy, water, and wastewater. Currently, net zero goals are a part of initial project-design discussions, but the expectation and desire to achieve these goals through feasible and cost-effective conservation strategies is gaining momentum. Although LEED certification is often desired by the owner, more emphasis is being placed on building performance rather than certification.

CSE: Tell us about a recent project you’ve worked on that’s innovative, large-scale, or otherwise noteworthy. In your description, please include significant details—location, systems your team engineered, key players, interesting challenges or obstacles, etc.

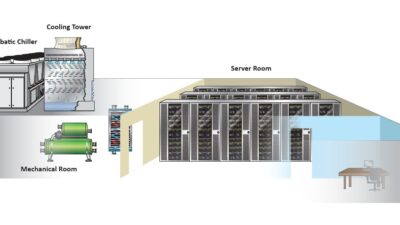

Heiple: We provided mechanical, electrical, plumbing (MEP); security system design; and construction administration for the renovation of the busiest Land Port of Entry (LPOE) in the world, located on the U.S.-Mexican border and maintained by the General Services Administration (GSA). We were involved in the project’s initial master planning and two of the design and construction phases. This project demonstrates how innovative strategies and team collaboration can evolve an initial LEED goal to deliver LPOE’s first and only LEED Platinum project in the U.S. It is designed to achieve net zero energy for conditioned spaces and net zero water for nonpotable water usage, and it will be a zero-discharge site for stormwater management. Unique challenges include phasing construction to maintain continuous operation, U.S. Customs and Border Protection security requirements, and mission critical systems. The existing inspection booths had air-quality issues with high levels of automobile exhaust that we addressed with a unique ventilation design. Some features instrumental in achieving performance goals are canopy-integrated photovoltaic (PV), vertical-loop geo-exchange systems with central plant heat recovery, and onsite wastewater treatment with a rainwater cistern that is also used as a thermal battery in conjunction with the geo-exchange system.

Lewis: In 2017, a new 101,000-sq-ft, state-of-the-art police headquarters facility was completed in Orlando, Fla. This project was performed as a design-build contract and achieved LEED Silver certification. H.J. High Construction served as designer-builder along with Architects Design Group in association with RTM Engineering Consultants. Located in downtown Orlando, the $34 million project replaces the existing outdated facility, which has been purchased for another use. The mechanical systems for this project used variable refrigerant volume (VRV) units to provide heating and cooling for the office areas and direct-expansion package units with energy-recovery ventilators for the multipurpose and lobby areas. There is a total of nine VRV systems. One of the main requirements for Orlando’s police headquarters included standby power in the event of a power loss. The initial design intent for this facility included the use of microturbines for power generation, but due to budget constraints, an emergency generator was used for standby power with the main power provided by the local power company.

Chang: The modernization of the Smithsonian Institution’s Renwick Gallery was recently recognized as a 2018 American Institute of Architects Committee on the Environment Top Ten winner, as well as a Beyond Green winner from the National Institute of Buildings Sciences, a knowledge-sharing portal developed originally for federal agencies. The Renwick Gallery required a historically sensitive, full-building modernization of a 19th century building. The project was developed with 50/50 public and private funding, blending the requirements of the Smithsonian, as a federal entity, with elements of a private-sector project. A significant mission of the project was to ensure future care and support for the building, given increasingly limited funding sources. One of the challenges was developing sufficient support for infrastructure-heavy projects when project backers also wanted to see the visible impact of giving. Prior to modernization, annual attendance was less than 50,000. The museum, with its most recent exhibit of the Burning Man, has seen more than 125,000 visitors in a 1-month period. The Smithsonian’s team structure allowed significant peer-to-peer collaboration, but it also required an experienced design and construction team that was used to working with large stakeholder groups to address a range of technical issues, particularly related to code compliance.

CSE: Each type of project presents unique challenges-what types of challenges do you encounter on projects for government, state, municipal, federal, and military projects that you might not face on other types of structures?

Heiple: For government projects within the U.S., compliance with the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act can sometimes be an obstacle to implementing advanced technologies; there are not enough qualifying manufacturers to facilitate competitive bidding. For large multiphase projects with multiple design/contractor teams, maintaining building-performance goals set forth in the master planning can be a challenge.

CSE: How are engineers designing such facilities to keep initial costs down while also offering appealing features, complying with relevant codes, and meeting client needs?

Chang: The use of an integrated design process with broad, early stakeholder engagement is essential to defining clear owner’s project requirements and a responsive basis of design. Engineered systems now represent more than one-third of the first cost of a new construction project and potentially more than 50% for a major renovation. It is critical to integrate engineering considerations early, to allow for a rightsized approach to system selection.

Heiple: Using integrated design strategies reduces initial cost while achieving the desired performance, such as integrating PV with shading structure, using water storage as a thermal battery to offset geo-exchange systems, and reducing generator-power requirements by using high-efficiency HVAC systems.

CSE: Have you worked on such projects for overseas clients? If so, how have you found project requirements compare between the U.S. and other countries?

Heiple: Yes, we have worked on projects for overseas clients. U.S. project requirements are typically more stringent for MEP systems.

CSE: The GSA and other agencies impacting government, state, municipal, federal, and military can be sticklers for detail. Do you find them to be more difficult to work with, or just different? How so?

Heiple: The government agencies we have worked with have talented engineers with a deep knowledge base on project-specific systems. As a part of the design process, we receive a lot of feedback on specific operational requirements. This review process is extensive and time-intensive, but it ensures that we meet the owner’s expectations and requirements.

Chang: The structured review processes used by many governmental bodies can be thorough, but they also allow for less likelihood of a misunderstanding between an owner’s intent and a design team’s interpretation. The GSA’s P100: Facilities Standards for the Public Buildings Service guideline has made strides to balance prescriptive requirements against performance-based outcomes. We have never seen a governmental process that restricts creativity, but rather allows for better change management and reduced risk for mismatched expectations at the end of a project.

CSE: For an engineering firm that has never bid or worked on a government project before, what suggestions would you offer to help prepare them to be eligible to bid and design?

Heiple: Encourage collaboration with your partnering design team and anticipate extensive feedback during the design-review process.