Applying thermal energy storage helps maximize efficiency and lower operational costs in the K-12 school market.

Learning objectives

- Understand the impact of demand charges on electricity costs for commercial buildings and how optimizing traditional HVAC systems has only a minimal impact on this cost for K-12 schools.

- Examine a real-world example of how thermal energy storage can dramatically reduce operational costs with limited to no increase in initial construction cost.

- Get a glimpse of the future as electrification of heat becomes the next generation of HVAC.

Thermal storage insights

- When cost savings through optimization of existing systems reaches its limit, thermal energy storage can result in significant financial windfalls for school districts by shifting most of their electrical demand to off-peak periods, a strategy both supported and endorsed by utilities.

- Adding ice tanks to a chilled water system can save money while cooling buildings through load shift strategies, while also serving as a bridge to advanced HVAC approaches that use thermal batteries to eliminate burning hydrocarbons for heating buildings.

The constant pressure to maintain operational standards while simultaneously lowering operational costs is by no means endemic to the world of public K-12 schools. However, when it comes to the specter of social backlash at the mere suggestion that a cost-cutting exercise is being considered, the K-12 vertical market stands alone. Cutting educational spending of any kind is almost certain to come with the challenge of doing so while overcoming resistance from parents, teachers, union leaders and even students.

For a school district looking to save money, it makes sense to focus on areas of their budgets that do not directly intersect with traditional educational considerations. While school districts can be vastly different, nearly every district in the United States has one thing in common: They own and operate buildings that come with significant operational costs. Reducing those costs can be a win for all parties. The district spends less money, while the stakeholders in the educational services being provided can rest easy knowing that money for textbooks, computers, athletics and teacher salaries are not impacted.

Operational cost considerations

When considering the operational costs of a school building or campus, electricity is the primary driver and the systems that are designed to provide heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) are typically the largest individual users of electricity. In warm and/or humid climates, energy used to cool the air distributed throughout school buildings can be particularly significant, often representing up to 25% of overall electricity usage.

Since the advent of microprocessor-based HVAC control systems in the late 1980s and networked building automation systems in the late 1990s, building operators have turned to advanced system optimization strategies. These approaches are rooted in programming and configuration to ensure that HVAC equipment operates as efficiently as possible and uses as little electricity as possible. While effective, this approach has a fundamental limitation.

Even the most optimized and efficient system must be capable of accommodating the building’s worst-case scenario cooling loads and operate at maximum capacity when those conditions are present. For a school, this high-load period is nearly always during the midafternoon of summer months. This dynamic comes with an inherent cost penalty for many districts due to its harmony with peak operational load windows of the utilities that provide electricity to the schools. This leads to significant demand charges.

Anyone who has reviewed their residential power bill is accustomed to being charged for usage in kilowatt-hours and the costs of fuel associated with generating the energy used. In concert with a baseline customer charge, this makes up a typical monthly statement. For commercial customers, there is often a fourth component — demand. In addition to being charged for the energy and fuel used, commercial buildings are typically charged a fixed value based on the highest instantaneous power draw in kilowatts (kW) over a rolling 15-minute window within the periods that the utility designates as peak hours.

Shifting peak power periods via thermal storage

With school buildings experiencing peak cooling loads during these windows, their peak power draw is driven by their combined HVAC systems operating at full capacity. For larger campuses consisting of more than 100,000 square feet of occupied space, this can mean a standing charge of tens of thousands of dollars per month because these sites tend to rely on chilled water-based cooling systems. While chilled water-based HVAC systems are often an ideal solution for many building types, the energy intensity of chillers can be a disadvantage when demand charges are high.

However, the use of chillers presents a design option that no other traditional HVAC approach offers. In theory, if the most energy-intensive operational point of an HVAC system could be shifted from on-peak periods to off-peak, then a building operator could avoid demand charges altogether. Thermal storage makes this theory a reality.

While holding classes in the late evening and early morning to avoid demand charges is not realistic for a K-12 school, shifting the peak demand draw of its HVAC system is. By selecting and installing chillers capable of cooling water to below freezing temperature, a strategy known as ice storage can be employed. Rather than using chillers during the day to cool the building directly, the chillers can be programmed to operate after hours, typically overnight, during the off-peak window of the servicing utility.

Cost-saving benefits

While a chiller configured for comfort cooling typically produces water in the range of 42°F to 45°F, a chiller configured for thermal storage produces water that is below 30°F. This water is then fed through a series of thermal storage tanks, each containing an independent internal reservoir of water. As the below-freezing loop of water passes through the tanks, the water inside the tanks freezes. A glycol or antifreeze solution is added to the chilled water loop to ensure the water in that loop stays cold enough to freeze the water in the tanks, while staying in liquid form itself to allow for flow through the system.

The tanks are heavily insulated so that the ice remains in a solid state for an extended period. This process is referred to as “charging the tanks.” Once fully charged, the energy expended by the chillers remains stored in the tanks for use the next day.

During the occupied operational period of the building, the same loop of water is pumped through the tanks, transferring energy back in by melting the ice that was produced the night before and thereby discharging the tanks. This cools that loop down to the required operational temperature for comfort cooling, allowing that water to be pumped to the building loads. In this configuration, the chillers remain off during on-peak operation. While the demand charge still exists, it is now driven only by the energy needed to pump water through the tanks and to the building loads. The chillers remain off, meaning that 100% of their load has been shifted to off-peak periods.

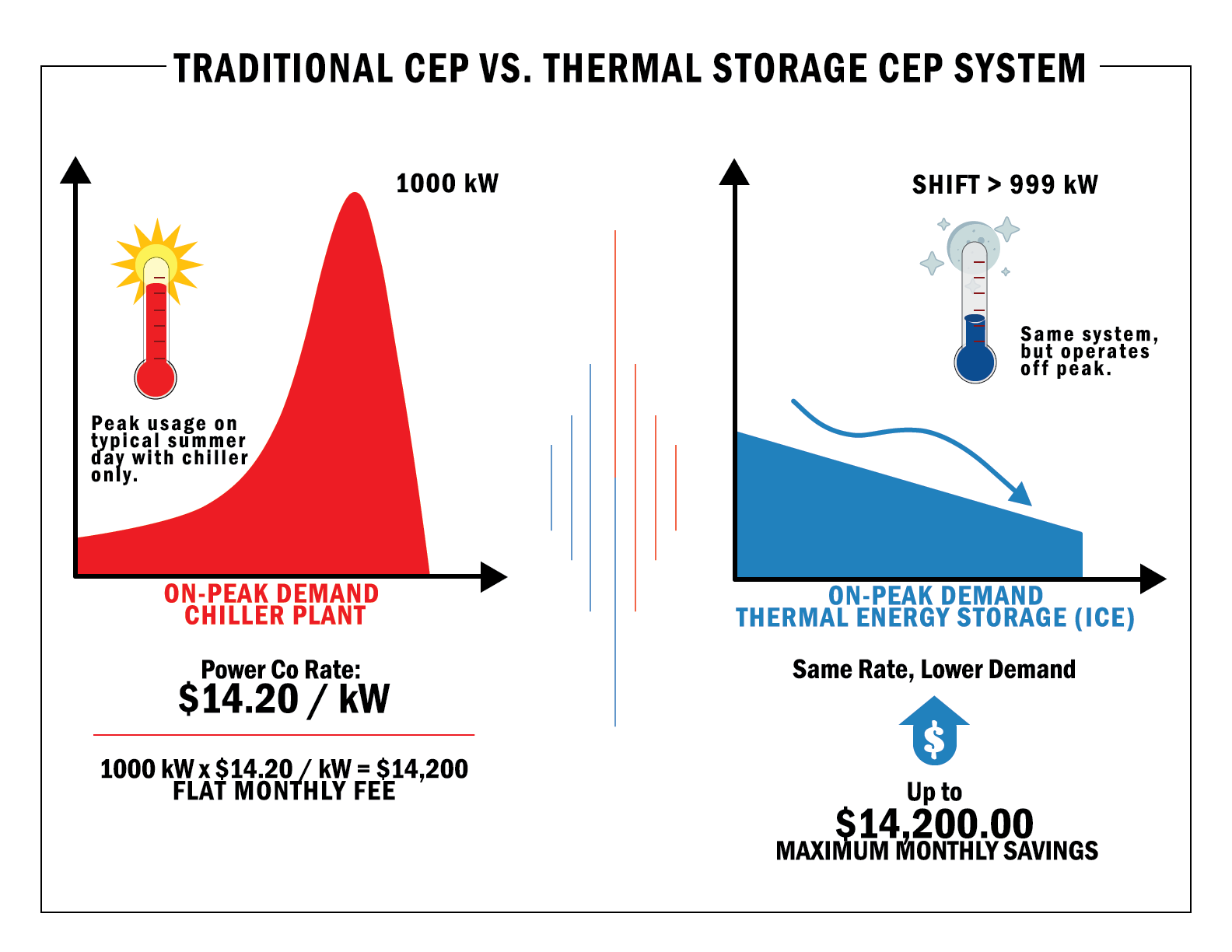

The cost benefits of this design approach can be demonstrated by considering the operation of a high school campus in Florida, which introduced a thermal storage solution. The local utility rates included a demand charge of $14.20 per kW. By shifting 788 peak tons of cooling capacity via ice storage, 1,000 kW of peak demand from the chillers was also shifted to off-peak hours. This resulted in monthly savings during the peak summer cooling season of $14,200 (see Figure 2).

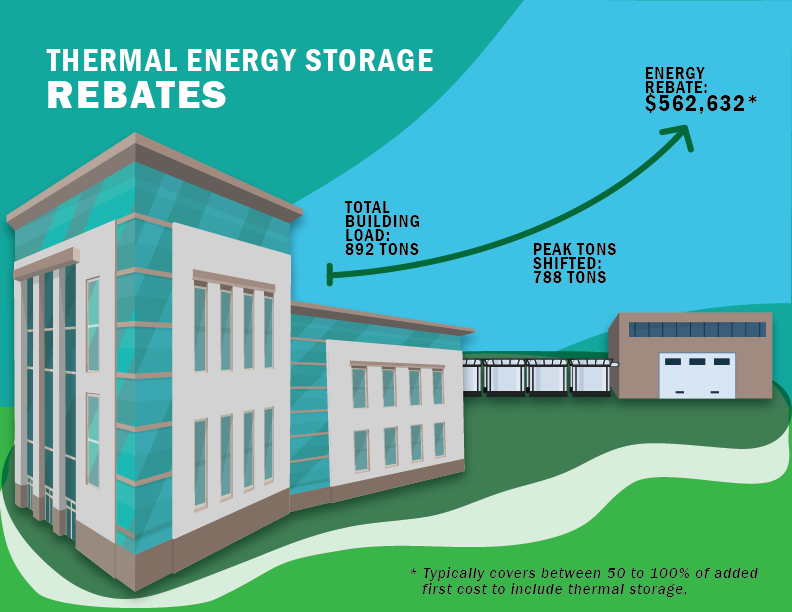

When considering the return on investment of such a design, it is key to note that most utilities welcome this shift in demand to their off-peak windows, so much so that many offer direct rebates to customers who employ this strategy. Depending on the building type and storage capacity installed, these rebates will typically cover between 50% and 100% of the delta in construction and procurement costs. In this case, the school district received a one-time rebate of $562,632 — enough to entirely offset the added first cost of an ice-storage system versus a conventional chiller plant (see Figure 3).

Note that direct chilled water storage, in lieu of ice tanks, is also a viable thermal storage strategy and utilities often do not discriminate between the two.

However, direct storage of high volumes of chilled water requires significant real estate to accommodate a tank holding millions of gallons of water, which is often not feasible in a K-12 application. The initial construction costs are also several orders of magnitude higher versus ice storage, making direct storage a viable solution for vast campuses such as universities and theme parks or industrial applications where chilled water is used for process cooling as opposed to comfort cooling.

Thermal storage as a first-line solution

While serving as a mechanism to lower operational costs, adding ice storage tanks to an HVAC system now may serve to future-proof it to handle ongoing challenges. While originally invented to shift cooling loads, the next generation of advanced, eco-friendly HVAC systems will employ ice tank technology to facilitate heating. As the push to eliminate the combustion of hydrocarbon-based fuels for heating grows, HVAC manufacturers are developing solutions that employ classic water-cooled chillers to serve as heating sources.

Rather than using a cooling tower to reject heat produced by a chiller to the atmosphere, this energy can be used to heat a building directly. With the chiller now acting as a heater, the chilled water side of the system can be tied to ice storage tanks. The system builds ice to heat the space. Heat pumps can then melt the ice to cool the space. In such a configuration, what was once an ice tank is now a thermal battery. With cost savings, energy efficiency and application of green building concepts becoming paramount to building operators, engineers must begin to consider thermal storage as a first-line solution rather than a niche application.