Boilers for heating and domestic hot-water systems are used in many hospitals and health care facilities. This looks at the codes and standards that regulate boiler specification, plus energy efficiency and efficacy of hot-water heating systems.

Learning Objectives:

- Identify requirements for a boiler system for heating and domestic hot water in a health care building.

- Analyze the codes, standards, and other requirements for designing boiler systems and their related HVAC equipment.

- Develop a design to maximize energy efficiency.

Hospitals offer a unique opportunity to be creative when designing a hot-water system. While providing reliable support for critical health care functions is the first priority, it is possible to design a system that significantly improves energy efficiency and cost-effectiveness by separating steam and hot-water systems and using condensing boilers configured to operate with maximum efficiency.

More than any other building type, airflow quantities in a hospital are dictated by code. Many of the spaces have minimum airflows regardless of the actual loads or the number of occupants. The Facility Guidelines Institute’s (FGI) Guidelines for Design and Construction of Hospitals and Outpatient Facilities” is the primary guideline being used today for hospital accreditation by The Joint Commission, and many states have either their own amendments or a complete alternate code.

FGI now references ASHRAE Standard 170: Ventilation of Health Care Facilities for the actual airflow requirements. All of the health care HVAC-related codes concentrate on the minimum acceptable airflow quantities for each type of space and the pressure relationship between the spaces. The codes also dictate the amount of air that is fresh outside air. Different systems have been used over the decades to meet these requirements, including constant-volume single zone, constant-volume multizone, dual-duct systems, and single-duct variable air volume (VAV) systems. In recent years, newer systems have been developed and tested including variable refrigerant flow systems and chilled beams. The majority of the health care facilities built within the last 20 years use a VAV system with hot-water reheat; therefore, this article will use this type of system as a basis for discussion.

VAV systems

When a VAV system is used in a health care facility project, the minimum airflow of the terminals is dictated by the space’s minimum airflow requirements. A portion of the terminal units is actually designed as constant volume terminal units, because the minimum airflow requirement exceeds the airflow required to meet both the heating and cooling load of the spaces. This results in the need for reheat all year. Coupled with the fact that domestic hot-water uses are constant throughout the year, a typical hospital may have a summer water-heating load that is two-thirds of the winter hot-water-heating load.

Hospitals, especially large ones (>500,000 sq ft), have an inherent steam requirement for sterilization-related equipment and the humidification of large outside air quantities. Because a steam system is necessary to begin with, there is a tendency to make it support a host of building functions. Historically, the steam system has been used to serve all functions requiring heat. These additional building functions can include kitchen, laundry, and typically all water heating. Domestic hot water and heating hot water are generated with steam using shell and tube or tank bundle-type steam converters.

This makes the steam system a major component of the facility, requiring trained and experienced boiler operators. Field-built water-tube boilers and manufactured water- and fire-tube boilers from 500 to 2,000 hp or more are present at most large hospital campuses. The inherent design of these boilers as noncondensing limits their efficiency, even in ideal conditions.

The age of the boiler, steam trap maintenance, and steam leaks all contribute to making the actual efficiencies of these systems much lower. Redundancy and system reliability have traditionally far outweighed any concerns over minor efficiency losses. However, times are changing, and an increase in efficiency of just a few percentage points is highly sought after.

Improving efficiency

A key strategy to improve the efficiency of heating systems for hospitals is to separate the heating water and the steam systems. In this new design paradigm, steam systems are downsized to meet only the direct steam requirements for humidification and sterilization. Hot-water systems for both domestic and hydronic heating, which had typically been generated through steam converters, are generated independently of the steam system using their own fuel source. This single measure—providing separate water boilers of the condensing type—gains several percentage points of efficiency for a large percentage of the facility heating needs. In addition, decoupling the heating-water systems from the steam system provides significant opportunities for the design professional to be creative when developing the most efficient system possible.

Condensing boiler efficiency is maximized when the temperature of the heating water returned back to the boiler is reduced below the dew point of the water vapor in the exhaust gases, which occurs at approximately 130°F. Condensing boiler efficiency improves as the inlet water temperature decreases, according to ASHRAE. The lower heating-water temperature causes the water vapor in the exhaust gases to condense. The condensate is then passed through a heat exchanger within the boiler, and the latent heat is recovered. In a conventional boiler system, this situation must be avoided because the condensate and residual air that remains after the combustion process causes damage to the boiler in the form of corrosion, failed refractory, and fin blockage due to sooting. While these potentially damaging conditions are still present in a condensing boiler, the boiler components and flue are constructed with corrosion-resistant materials to prevent corrosion and destructive effects.

These efficiency characteristics encourage the designer to drive the heating-water-return (HWR) temperature as low as possible. The first step is to evaluate the climate conditions to identify if the hot-water system can be designed to operate at a supply temperature that is closer to the exhaust gas condensing point. Ideally, the system can be designed to work with 140°F supply temperature with an HWR temperature within the 110 to 120°F range on a design heating day. These operating temperatures are especially practical in southern climates with milder winters.

However, designing with a lower hot-water temperature requires a careful analysis of the system heating coils. The lower hot-water temperature causes a reduction in “approach,” the term given to the difference between the hot-water-supply temperature and the temperature of air entering the heating coil. Due to the lessening of the approach, more coil surface area is required to obtain the same heating capacity versus when 180°F water is supplied to the reheat coil. To counteract this reduction in coil capacity, three-row coils may be required.

Another potential solution is to upsize the terminal box to increase the coil surface area. For example, a 6-in. terminal box with a two-row coil may be adequate to meet the airflow requirement, but may not have enough coil surface area to meet the discharge-air temperature requirement with 140°F heating-water supply (HWS) on a design heating day. To avoid upsizing to a three-row coil, it may be possible to provide an 8-in. terminal unit with a two-row coil. The cost of this upsize is minimal (10% to 20% of terminal box cost) and avoids the additional fan energy consumption required to overcome the increased pressure drop of a three-row coil. This additional cost is quickly offset via the efficiency gained by operating the condensing boilers at a higher efficiency range.

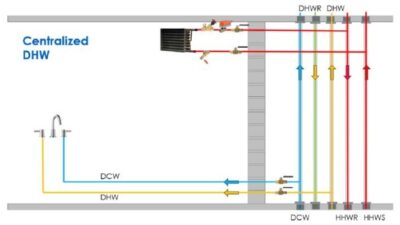

There are additional creative ways to drop the HWR temperature even further. Within a health care facility application, there are multiple systems that require heat with a consistent load profile that can serve as a heat sink for the HWR. These systems can include domestic hot-water heating, steam system make-up water preheating, snow-melt systems, and in-floor radiant heating systems. Each of the aforementioned systems can be intercepted and piped through individual plate-and-frame heat exchangers. The heating water can then be connected to the other sides of these heat exchangers, piped inline or in a side-stream configuration with three-way valves or inline pumps.

A simple example is the preheating of domestic cold water before it is sent to the domestic water heater. A conventional water heater will operate with similar efficiencies to that of a conventional boiler in the 80% to 85% efficiency range. Condensing water heaters are also available, which can operate in the same efficiency ranges as a condensing boiler (approximately 98%). However, efficiencies of a condensing water heater can be limited in part-load conditions due to the constant recirculation of hot water from the building and the intrinsic storage component of a water heater.

In a health care facility application at part-load conditions, domestic cold water between 40° to 60°F is mixed with water returning from the building between 110° and 120°F before entering the domestic water heaters. While this mixed temperature of water still allows condensation of water vapor in the flue gases for energy recovery, further efficiency can be gained if the make-up water is preheated by the HWR via a double-wall plate-and-frame heat exchanger. The water heaters are then used to boost the domestic hot water to a minimum temperature of 140°F, which is necessary to eliminate Legionella bacteria from building up in the hot-water system.

This system configuration maximizes the efficiency of the condensing boiler, whose operation is required regardless of the presence of the heat exchanger and, at minimum, limits and potentially eliminates firing of the condensing water heaters, which are operating a lower efficiency point. No equipment is more efficient than equipment that doesn’t have to operate; this statement is not intended to discourage the use of a condensing water heater, but rather to place greater emphasis on system energy performance over component energy performance.

Implementation of an HWS temperature reset is also vital in reducing HWR temperature. In a traditional heating-water system with a fire- or water-tube boiler, the minimum limit that the supply heating-water temperature can reduce must be limited to prevent the HWR temperature from causing condensation in the flue and, in turn, damaging the boiler. In a condensing boiler system, there is no minimum limit and lower temperatures are encouraged.

Heat-recovery chillers

There is an additional technology available that can be implemented into the aforementioned system that can create heating water. In a health care application, there is often a year-round requirement for chilled water similar to that of heating water. The use of air-side economizers must be considered in this analysis in many climates, as outdoor weather conditions may allow the chilled-water system to be disabled completely. But when there is a demand for year-round chilled water or a water-side economizer is present, the incorporation of a heat-recovery chiller can allow for tremendous system efficiency gains.

A heat-recovery chiller creates chilled water at typical chiller-water temperatures while transferring the heat from the chilled water to a water-source heat sink. This operation is similar to that of a typical water-cooled chiller, but instead of discharging water at 95° to 100°F, it can discharge water from the heat sink side at temperatures up to 140°F. This hot water can then be recovered in the form of heating hot-water supply, or at minimum, a hot-water booster prior to the boilers. It should operate at the same working temperatures on the hot-water side to that of the condensing boilers, which provides for a harmonious integration of a heat-recovery chiller into a condensing boiler heating-water system.

The design of the heat-recovery chiller in this type of application must be approached with care. It ideally needs to be sized to hit the “sweet spot” of the minimum of either heating load or chilled-water load that allows it to run 24/7. Given that the heat-recovery chiller is intended to be supplemental to chiller and boiler systems, any remaining heating or cooling of the water necessary will be handled by the boiler or chiller systems.

It is important that the heat-recovery chiller in this application not be grossly oversized, as it will operate to its minimum heating or cooling load. The outcome of the significant oversizing is the potential for portions of the equipment capacity to be untapped in typical cooling or heating conditions. While this may not seem like a significant drawback, the reality is that loss of run time hours negatively impacts the equipment return on investment.

The initial cost of heat-recovery chiller equipment is expensive as compared with the cost of a boiler and chiller at similar capacities. From an operational standpoint in comparison with a traditional system, a heat-recovery chiller acting solely as a chiller is an inefficient chiller, and a heat-recovery chiller acting solely as a boiler is an inefficient boiler. However, when it is acting as both a chiller and a boiler simultaneously, it is significantly more efficient than operating independent chillers and boilers simultaneously (see Table 1). In a health care facility application where the heat-recovery chiller is intended to operate in a supplemental energy/cost-saving capacity, it is probably the only example of equipment where slight undersizing is desirable as opposed to oversizing. A properly sized heat-recovery chiller system can attain a payback within 5 years, especially in instances where the natural gas cost is greater than 33% of the cost of electricity per the same energy unit (comparative dollars/Btuh).

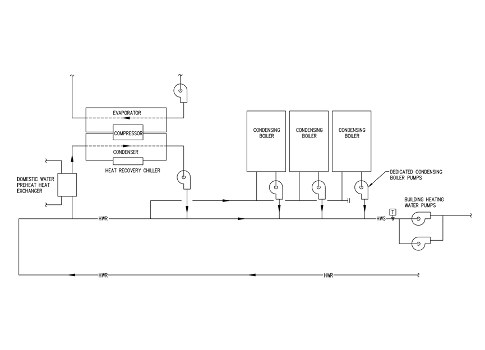

The integration of the heat-recovery chiller into the condensing hot-water boiler system also can be piped in such a way as to optimize the efficiencies of both the heat-recovery chiller and condensing boiler systems simultaneously. In Figure 1, both the heat-recovery chiller and condensing boilers are piped in side-stream configuration off of the main heating water loop. The piping feeding the condensing boilers connects to the main HWR prior to the discharge point of the heat-recovery chiller back into the main water system. This allows both the heat-recovery chiller and condensing boilers to receive cooler HWR, thus maximizing the efficiencies of both systems.

In addition, the pumps dedicated to the condensing boilers allow for significant turndown of the flow-through boiler, which further increases boiler and system efficiency. The heat-recovery chiller operates to achieve maximum possible heating output, and the condensing boilers provide as much heat as necessary to reach the heating-water system setpoint.

The alternative would be to pipe the condensing boilers in series with the main heating-water system, which aligns with a more traditional heating-water-system layout. The heat-recovery chiller would still be configured in a side-stream capacity, but the condensing boiler system would receive heating hot water after it has already been conditioned by the heat-recovery chiller. This configuration allows the savings of the dedicated pumps required for each boiler, but does have the potential to raise the hot-water inlet temperature to the boiler above its condensing point in part-load conditions.

There are also creative means that can be employed when adding on to heating-water systems that have been designed around more traditional HWS and HWR temperatures (i.e., 180°/150°F HWS/HWR) to drop the HWR temperature and make condensing boilers and heat-recovery chillers possible. First, a careful analysis of the existing system heating coils is required to determine the minimum discharge-air temperature necessary to meet the space-heating load. Once this value is determined, an analysis of the heating coils must be performed to determine what discharge temperature the coils are capable of at various hot-water supply temperatures.

Due to the code-required minimum air-change rate in many spaces in health care facilities (especially those that require constant-volume systems), the terminal box discharge temperature required to offset space-heating requirements may only be in the 80° to 85°F range, especially in southern climates. Heating-water flow through the boxes also must be considered when performing this analysis, as the flow will inevitably increase as the hot-water supply temperature is reduced. If it can be determined that the system supply temperature can be reduced to 150°F or less, it provides an opportunity for condensing boilers and a heat-recovery chiller to be employed.

In the aforementioned design condition, reducing the HWS temperature to 150°F alone may not be enough to ensure that the heat-recovery chiller is operable 24/7, as the HWR temperature may still be too high (130° to 140°F). In addition to employing the previously described strategies to reduce the HWR temperature, any new building additions can be provided with dedicated secondary hot-water loops that blend the 150°F supply water into the new secondary loop to maintain the new design secondary loop supply temperature (see Figure 2). This configuration permits each secondary loop to operate with its own HWS temperature setpoint and allows temperature reset within each loop.

In conclusion, the minimum air changes required in health care projects result in needing heating water year-round due to reheat loads at minimum ventilation. This creates an opportunity for the design engineer to develop creative ways to meet that heating load. Incorporating any heating load that can reduce the HWR temperatures allows efficient use of condensing boilers, heat-recovery chillers, and other creative solutions.

Wyatt Wirges is a mechanical designer at WSP + ccrd. He has been involved in the design and analysis of both mechanical and plumbing systems in health care applications across the country. Jay Goode is a vice president at WSP + ccrd. He has designed and commissioned mechanical systems for both small and large health care projects across the country over the course of his 28-year career.