Smart building design requires a smarter approach. Proactive design and operational decisions can realize a smart building.

Learning objectives

- Understand why new buildings today aren’t just “smart by default,” despite the presence of advanced technologies.

- Evaluate how building designers must evolve their practices to fully leverage an outcome-based approach to modern digital technologies in the built environment.

- Identify the organizational shifts needed across building owners, operators and occupants as well as the broader design industry to realize the potential of modern smart buildings and challenge the existing conventional practices.

Smart building insights

- Smart buildings require a different relationship between building designers, owners and operators and their built assets, with closer coordination between phases and a clearer definition of shared goals across stakeholders necessary for successful smart technology interventions.

- Modern buildings are no longer static monuments to a design philosophy — they are dynamic, data-driven entities that are expected to evolve as quickly as the functions they house.

Digital technology has been shaping the built environment for decades. Yet, the buildings industry has not fully embraced the potential of smart buildings to truly maximize this impact.

Design and construction partners, as well as building owners themselves, must adapt to ways of working that are better suited to digitally enabled outcomes for buildings. Otherwise, the buildings industry will continue to lag other industries, missing out on the adoption of technology and the efficiency gains that come with it.

The real estate technology market in 2025 continues to experience strong growth, lively mergers and acquisitions activity and exciting innovation and development, partially due to the proliferation of artificial intelligence (AI). Building owners and operators have a variety of tech-enabled options to choose from in selecting solutions for their business needs, from more traditional electronic systems to emerging building management apps. Available technologies — plus more to come — can work in concert to create a smart building.

However, unlocking the benefits of these digital systems will require first changing status quo operating models to reflect the rapidly evolving technology landscape. Designers, owners and operators must work together to build and operate smarter buildings.

What is a smart building?

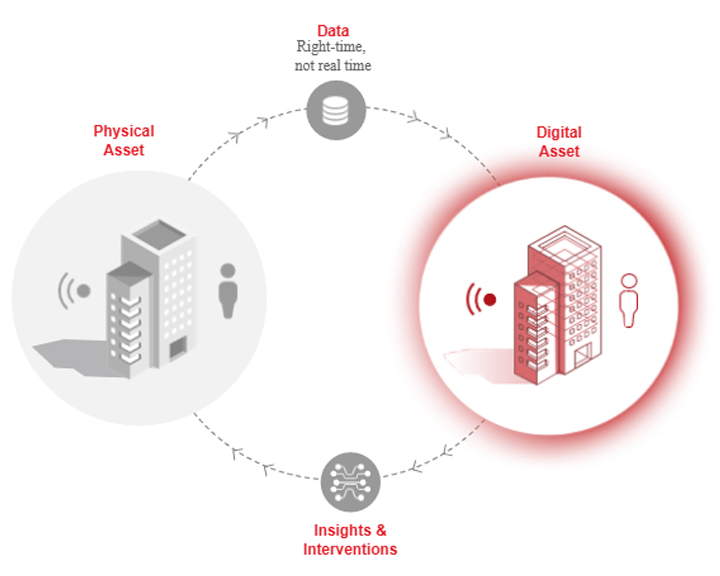

A smart building is one that leverages modern digital technology and a robust, secure set of actionable data to deliver benefits in two primary ways. First, it creates superior user experiences for building occupants. Second, it offers more efficient, manageable performance outcomes for building operators and owners.

More than any one solution or product, a smart building embodies an organization’s commitment to embracing digital ways of working, understanding how to make our built environment better meet human needs while ensuring that design and operating decisions made throughout the building’s life cycle are truly sustainable. The most successful smart buildings are the result of a commitment to a coordinated design, construction and operating process. The design of smart buildings should prioritize outcomes-based decision making and a technology foundation design that can meet needs while having the flexibility to adapt to the needs of tomorrow (see Figure 1).

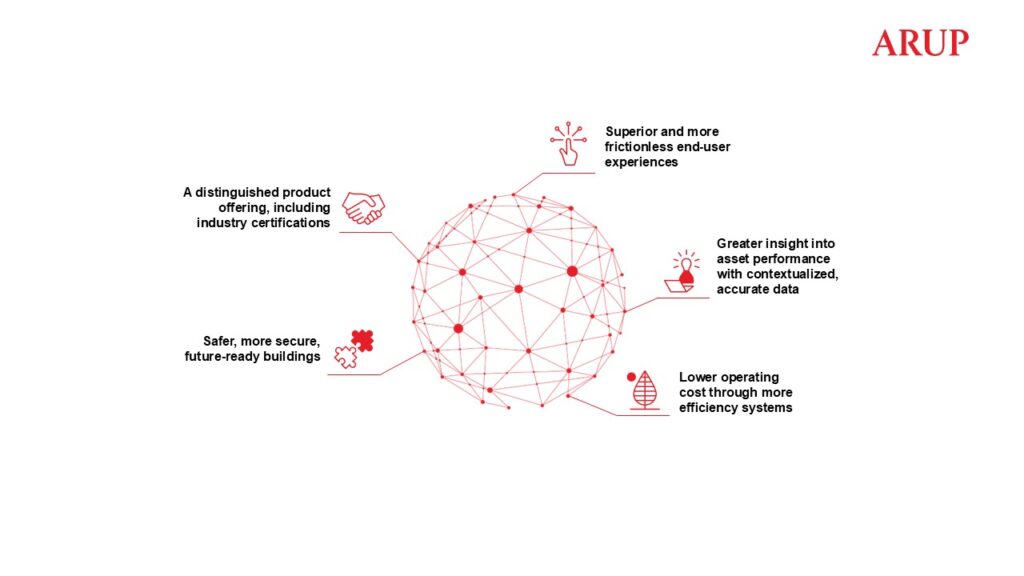

The values that smart buildings can provide versus a “business-as-usual” approach include:

- Lower operating cost through more efficient systems

- Superior and more frictionless end-user engagement

- Safer, more secure future-ready buildings

- Greater insight into asset performance with contextualized, accurate data

- A distinguished product offering, including industry certifications and ultimately more valuable assets.

Smart buildings provide their signature superior user experiences and better operational outcomes through a series of technology interventions — systems and sensors, apps and platforms, workflows and processes — designed to support and solve real use cases and business challenges. The design, procurement and implementation processes that result in these outcomes require responsible stakeholders to collaborate on defining a guiding vision for what “smart” means to any building and then empowering the buildings teams to take the action necessary to realize this vision.

Why aren’t modern buildings smart by default?

For many modern buildings, the technology infrastructure for smarter operations is already in place — but it’s not being leveraged. Almost every building built today and most building upgrades and retrofits is packed with digitally enabled systems that collect and analyze data, performing some level of automated operations and are typically equipped with internet connectivity or an app for user interface.

The price point of device-scale electronics with onboard diagnostics and communication capabilities has allowed the market to turn previously analog devices into intelligent, communicating endpoints. Additionally, the processing power of both on-premises computers and the accessibility of cloud-computing services allow system vendors to economically perform powerful analysis on the data generated or collected by smart end points in near-real time.

While these features becoming more common would suggest digitally native operations is a default state, the reality is that many features go unused or at least unoptimized and the true power of installed systems is not yet fully realized. This mismatch between installed capabilities and real-world operations has many causes:

- Lack of early-stage requirements definition

- Poor translation of desired features into project specifications

- Insufficient handover and training between design, implementation and operating teams

- Inadequate knowledge transfer between vendors, designers and operators

- The “performance drift” inherent in buildings naturally evolving away from their design setpoints as they age.

Making this problem harder to solve is the siloed nature of the built environment supply chain. From separated design disciplines to discrete contractors and trades, to specialist operations departments, there is rarely a single consolidated entity across a building’s life cycle tasked with and empowered to pull the various influences on digital systems in the same direction.

Can the design, construction industry help make buildings smart?

Simply specifying “smart devices” or requiring systems to come equipped with native application programming interfaces is not enough to make our buildings truly smart and prepared to adapt to the rapidly evolving demands placed on our built assets. After all, many buildings in operation have smart-ready systems but are operated as if they do not.

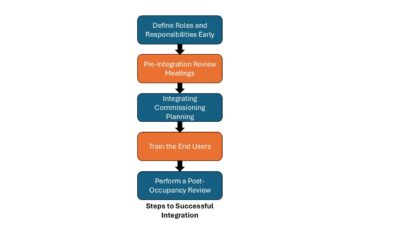

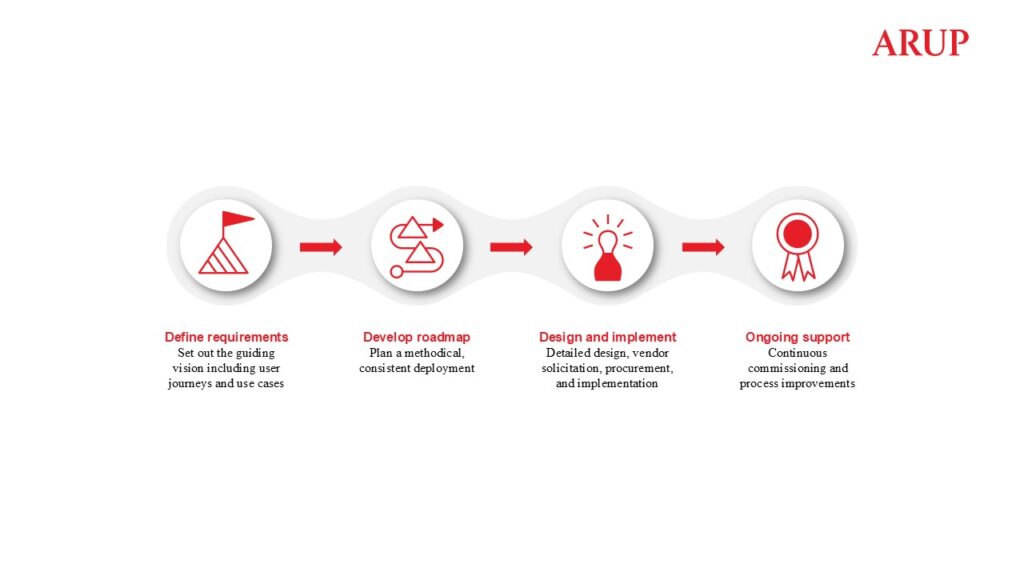

Design professionals responsible for shaping the built environment — architects, engineers, consultants, designers and product specialists — must embrace the opportunities that integrated, digital technologies present and adapt to the new ways of working needed to realize them (see Figure 2).

Design solutions that meet real, defined operational needs and are ready to face future challenges: Simply relying on design standards, typical details or the last project’s design approach will result in more buildings underusing even more digital platforms. This process starts early in a project’s design process and should include a concerted effort to program all building elements — not just spaces and layouts — to meet a client’s needs. Designers should present to the owner how a smart building’s design approach can result in more frictionless and intuitive interactions and more sustainable operating models. From there, designers can ensure these design principles are detailed in drawings, specifications, shop drawings and into implementation and handover.

One helpful step is establishing a collection of guiding — or exhaustive, if possible — use cases that illustrate the kinds of outcomes that will result in a successful project. These use cases should be specific enough to support the further design and specification of solutions or interventions needed to enable them, but not so specific that they lock a stakeholder group into only one option. Use cases should be defined with the ultimate business outcome in mind, establishing the ‘north star’ that provides guidance for all project design and construction efforts. When done correctly, beginning a project with a holistic definition of desired use cases and outcomes will provide a flexible and robust framework within which solutions, whether they’re digital or not, can be designed.

Design cross-discipline, integrated solutions: One of the key principles of smart buildings solutions is integrated systems. While integration can take many different forms, in concept, the design intent is for disparate systems and platforms to be natively connected such that they can share data and participate in complex workflows more fluidly.

From the traditional, “Why can’t my lighting occupancy sensor control turn on the heating, ventilation and air conditioning in my office?” use case, to more complex workflows, such as real-time locationing services in a hospital that trigger automated patient infotainment alerts, secure and intentional systems integration is an enabling design principle upon which smart buildings use cases can be built.

Such integration, however, is not necessarily status quo for design professionals, many of whom have discrete disciplines or roles and are responsible for ensuring clear scope delineation boundaries in their design documents. This must change. Clients who own and operate buildings do not view their core business as a collection of disparate components that make up a building and their design teams must not either. As architects, engineers, specifiers and installers, we must begin to identify the ways in which our various disciplines are complimentary and how they can both serve their core function while also serving as part of the broader ecosystem of integrated components.

Engineers also owe it to the industry to be clear and transparent about how the standard design engagements do — and do not — support integrated solutions. Design and construction contracts are often intentionally siloed, with scope delineations clearly identified and while this helps manage scope and responsibilities, it can lead to chasms in functionality if the gaps between scopes aren’t filled.

Many systems and platforms now depend on some level of support from an organization’s information technology (IT) department to function (e.g., network connectivity, internet access) and the IT scope handoff can be messy if not addressed proactively. Design professionals must engage with this lack of clarity and strive to deliver a built product that is complete, integrated and holistic.

Address the return on investment (ROI) early: The hardest budget line item to defend is the one that should exist but doesn’t. Smart-enabled system features are more commonly provided as out-of-the-box options with modern building products. If they are not selected and supported intentionally, they are likely to be underused or unsupported, leading to their failure.

Designers have a responsibility to help inform project teams of the true and holistic cost of design decisions, whether that is by identifying both capital and operating expenditure costs for specified systems or by separating the cost associated with a system’s core functions from additional costs and features that may come along with certain selections.

This adjustment will allow project stakeholders to better defend design decisions and support a more accurate calculation of return on investment or ROI — one of the most powerful design tools we have at our disposal. As many of the benefits of smarter, better integrated building technology systems are realized in the form of operational savings or enhanced revenue streams in operations, an ROI assessment must extend beyond a project’s design and construction timeline.

Frequently, smart buildings interventions are viewed as purely an additional cost that otherwise wouldn’t have been included in a traditional buildings project. Projects have been bearing the cost of enhanced, smart-ready features without fully realizing it for years.

By highlighting the ROI discussion early and honestly assessing the cost of core functionality versus the benefits of enhanced, integrated features, design teams will better equip owners and operators with intentionally selected systems and in doing so, raise the bar for the building’s status quo moving forward.

What is needed from building owners, operators to make buildings smart?

Once smart buildings aspirations have been identified as a priority, building owners, operators, developers and other stakeholders responsible for real estate design and planning decisions should first brace for some pushback. Change is hard and the buildings industry has more than a century of inertia to overcome before achieving a more sustainable future enabled by smart technology. With the right team of designers, builders, vendors and service providers assembled, owners can begin their journey to a smarter future.

Identify a champion: Like any organizational initiative, a smart buildings program requires support. Having a clear champion identified to spearhead the program and empower them to engage the right stakeholders across the organization to make decisions will lead to the best outcomes. This champion may come from a variety of backgrounds and for example, organizations’ smart buildings programs have been led successfully by:

- Facilities managers striving for better control over their buildings

- Real estate planners intrigued by the potential of data-driven leasing and operations

- IT stakeholders responsible for the day-to-day operations of their corporate IT networks

- Multimedia managers looking to enhance digital engagement.

Two important characteristics shared across all these champion types are their belief in the long-term value of smarter, more integrated digital systems and their tenacity to push for solutions even when they’re frequently met with “no” as an answer.

Mobilize the network: The success of a smart buildings program cannot be measured by the results of a single project. Similarly, a single person is unlikely to be able to carry the full weight of realizing the integrated, efficient future of smart buildings. Smart buildings champions must therefore be supported by a network of appropriately authorized stakeholders within an organization to make decisions and enact change.

Because smart buildings interventions can touch many different business functions, organizations wanting to realize the benefits of a smart building should empower a network of people across their organization to advance initiatives. These stakeholders do not have to be techno-experts or even smart buildings enthusiasts, but they should be immersed in the business enough to identify where smart buildings interventions may help and be willing to take action to realize such interventions.

Some stakeholders will experience a greater impact to their day-to-day duties because of the smart buildings initiatives. Building engineers and facilities managers should be engaged from the early use case definition process to ensure their operational needs are being addressed and their buy-in is incorporated into a smarter, digitally enabled operating model.

Support the ongoing evolution of the smart buildings program beyond Day One: While it can be relatively straightforward to muster enthusiasm and support for smart buildings initiatives on a capital improvement project, the ongoing support of these initiatives is where things can start to unravel. Buildings are not static monuments to a design approach and the things that give them their character require ongoing support.

The role of the smart buildings champion should not be limited to just design and construction projects. Rather, their remit should extend into the operational life cycle of an organization’s built assets. As user groups’ needs change or as new features or services become available in the market, use cases should be revisited or reestablished to ensure they are still relevant and impactful.

For owners or operators of a portfolio of buildings, a portfoliowide smart buildings program offers the opportunity to fine-tune smart buildings interventions over time and create a portfoliowide standard for digital platforms.

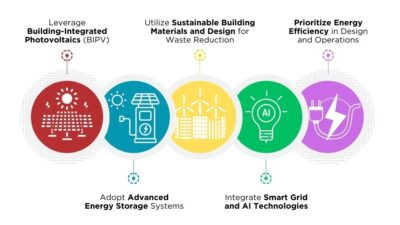

How to achieve the end-game of a smart building

Embracing the organizational change needed to realize smarter, more sustainable buildings can seem daunting, but there are accessible entry points for all types of buildings, building owners and operators. Pilot deployments can be used to validate functionality and prove out ROI, selective renovations can be used to establish design standards for major capital improvement or new-building projects, industry case studies can illustrate how other market players have begun their smart buildings journeys and digital twins (see Figure 3) and visualizations can be used to illustrate the effects of smart buildings interventions without needing to swing a hammer.

What’s critical across all these first steps is that an organization is clear on why and how: “Why are we interested in undertaking a smart buildings program?” and “Once we know what we want, how do we achieve it?” This clarity of vision will provide the direction needed to guide design and implementation teams to help realize a truly smart building.