Laboratory design is being transformed by smart building technologies.

Learning objectives

- Understand how the International Building Code consistently governs chemical storage and use in laboratories and how smart monitoring tools can support compliance with maximum allowable quantities.

- Identify best practices in laboratory design for ergonomics and circulation planning that improve safety, visibility and technician efficiency.

- Evaluate how smart building systems, such as intelligent building automation systems, real-time locating, smart lighting and integrated exhaust controls, enhance safety, sustainability and operational resilience in regulatory laboratory environments.

Laboratory design insights

- Laboratory design for public utility regulatory facilities must balance chemical hazard control, ergonomic workflows and integration of smart building technologies to ensure safety, efficiency and regulatory compliance.

- Effective laboratory design also requires close coordination among owners, designers and authorities having jurisdiction to manage chemical inventories, optimize layouts and implement intelligent systems that enhance performance under demanding operational conditions.

Public utility regulatory laboratories are mission-critical environments where the stakes for safety and performance are exceptionally high. These spaces must protect technicians from chemical hazards, support efficient testing workflows and comply with rigorous codes and standards while operating under tight budgets, schedules and public accountability.

Achieving this balance requires attention to three interdependent dimensions of laboratory design: chemical storage and use, ergonomics and layout and smart building technology integration.

Chemical storage and use

The safe containment of hazardous materials is one of the most critical aspects of laboratory design. Regulatory laboratories regularly manage hundreds of chemicals that span nearly all International Building Code (IBC) hazard categories, including flammables, corrosives, toxics, oxidizers and unstable reactives. Each category carries its own unique risks, which must be addressed through careful segregation, spill containment, proper exhaust and ventilation and continuous monitoring.

Because of the scale and complexity of chemical use, oversight is essential. Authorities having jurisdiction (AHJs), fire departments and laboratory health and safety teams must be able to track, monitor and fully understand the hazards associated with chemical storage and handling. Clear documentation and transparent communication between these groups and the design team provide the foundation for safe operations.

While designers play a critical role in documenting, sorting and categorizing chemical use to comply with building codes and safety standards, it is ultimately the owner’s responsibility to identify which chemicals are present and in what quantities within the lab. The design team assists by evaluating how to manage that inventory in a manner that meets code requirements and creates a safe, functional environment for laboratory staff.

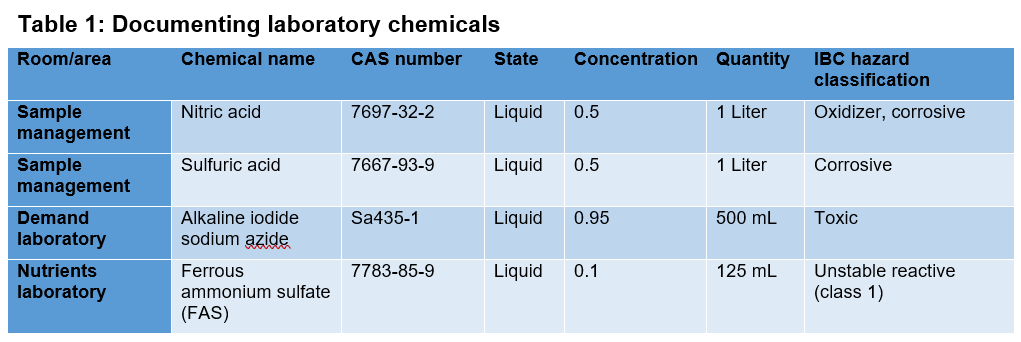

Organizing chemical information in a structured format not only supports compliance but also enables better decision-making during the design phase. The IBC requires that laboratories track both the storage and the use of hazardous chemicals, distinguishing between closed storage (sealed containers) and open use (chemicals actively in process, exposed or transferred). Each chemical must be classified and its quantity recorded to ensure compliance with the maximum allowable quantities (MAQs) set by the code.

Term definitions:

- Storage: Any portion of a building or structure where liquids, gases, solids or semisolids are placed temporarily for safekeeping or use.

- Closed system use: Use of a solid or liquid in a closed vessel or system that remains closed during normal operations where vapors emitted by the product are not liberated outside the vessel or system and the contents are not exposed to the atmosphere during normal operations. Examples include use in a sealed reactor or piping system.

- Open system use: Use of a solid or liquid in an open container or system where vapors may be emitted to the atmosphere during normal operations. Examples include open tanks, dipping or spraying operations or mixing in open vessels.

To evaluate whether laboratory hazardous chemical storage exceeds the MAQs per IBC 2021, NFPA 45: Standard on Fire Protection for Laboratories Using Chemicals and a series of other applicable NFPA standards — and to adjust the storage to remain compliant — focus is placed on storage quantities, as open and closed use typically involve smaller amounts in laboratories.

This would be different for industrial and manufacturing where chemical quantities are typical of greater quantities. The goal is to compare stored quantities against IBC 2021 Table 307.1(1) (physical hazards) and Table 307.1(2) (health hazards) MAQs, then propose adjustments such as using approved storage cabinets (to achieve a 100% MAQ increase) or separating the quantities into additional control areas to stay below the limits.

It should be noted that adding control areas under the 2021 IBC, International Mechanical Code and International Fire Code (IFC) introduces significant mechanical, electrical, plumbing and fire protection complexity due to the need for dedicated exhaust and makeup air systems, pressure control, fire-rated separations, specialized electrical and alarm interlocks and upgraded suppression systems (see Table 1).

Once all chemicals are properly classified by their physical and health hazards, the total quantities must be compared against the code’s allowable limits. If those limits are exceeded, several strategies are available. One option is to reclassify the space as high-hazard (H) occupancy, although this can trigger significant code requirements across the entire building. Another option is to divide the laboratory into multiple control areas, taking advantage of allowable increases for sprinklered buildings and the use of approved storage cabinets.

Other solutions may be possible depending on the laboratory’s size, layout and operations. What matters most is that the design team delivers a safe approach that is coordinated with the AHJ and with owner health and safety staff. This coordination often leads to greater owner awareness of their operations and, in some cases, improved practices, such as storing bulk chemicals in higher-hazard rated areas while limiting laboratories to smaller daily-use quantities.

In addition to chemical storage considerations, laboratories frequently use compressed gases, such as argon, hydrogen, nitrogen and others, that introduce unique safety challenges. These gases may present asphyxiation, flammability or pressurization hazards depending on their properties and intended use.

To mitigate risks, a detailed analysis should be performed in accordance with the IFC, NFPA standards and applicable national and local codes. This evaluation should include classification of each gas per NFPA 55, determination of maximum allowable quantities and control areas per the IBC and IFC and identification of appropriate exhaust and ventilation strategies — such as dedicated gas cylinder rooms or ventilated gas cabinets for hazardous or flammable gases.

Compliance options may include installation of continuous gas monitoring systems with automatic shutdown interlocks, provision of emergency power for exhaust and alarm systems and segregation of gas distribution piping within rated shafts or protective enclosures. Integrating these measures into both the building systems and the laboratory layout ensures that gas-related hazards are properly contained and that occupants are protected under both normal and emergency operating conditions.

Ergonomics and layout in laboratory design

A safe and efficient laboratory depends as much on its physical layout as it does on its chemical storage protocols. Thoughtful ergonomics and circulation planning create a work environment that reduces risks, minimizes disruptions and supports the precision required for regulatory testing.

In many ways, the way people move, see and interact with equipment in the laboratory is just as critical to safety as how chemicals are stored and used. Accessibility is also a key factor, with Americans With Disabilities Act-compliant circulation, counter heights and nonslip surfaces ensuring that laboratories are safe, inclusive and usable for all occupants. These considerations reinforce both regulatory compliance and day-to-day safety.

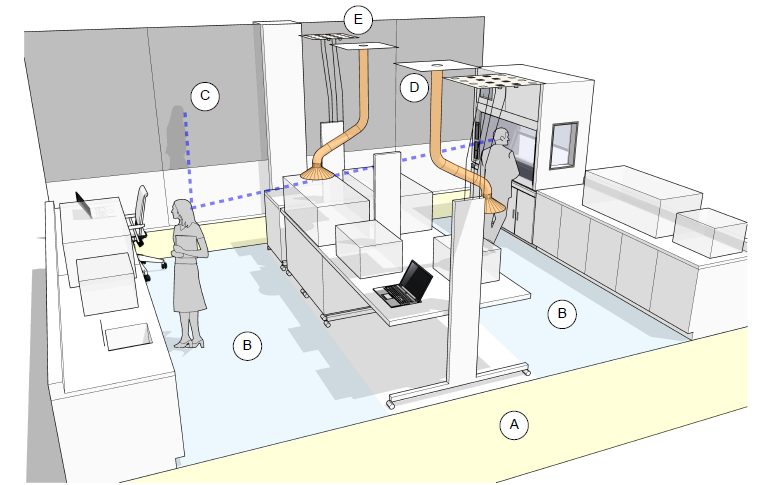

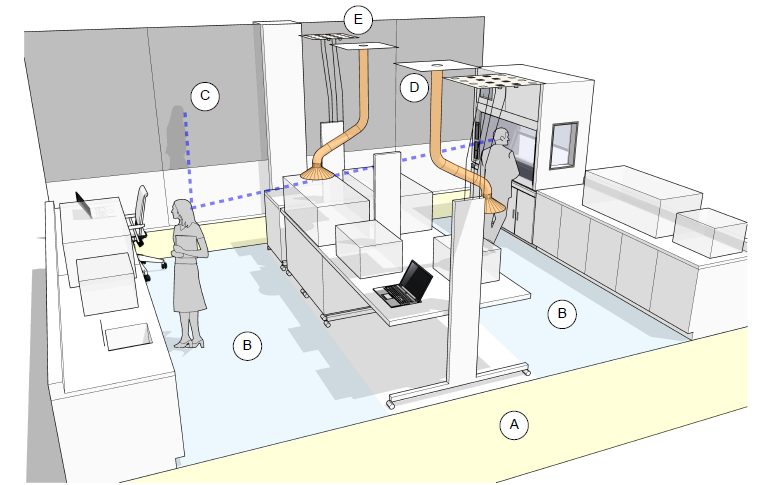

The following are key defining features of modern laboratory design:

Visibility and communication: Clear lines of sight across the laboratory, made possible through glass partitions and interior windows, allow supervisors and colleagues to monitor activities from multiple directions. This openness improves collaboration, reduces isolation and ensures that potential safety issues are detected quickly. In an emergency, visibility across spaces can save precious seconds in responding effectively.

Circulation and spacing: Laboratories must provide ample clearance around benchtops, casework and analytical equipment so that technicians can move freely without the risk of bumping into one another or obstructing equipment operation. A 6-foot clear workspace width is ideal to support both individual tasks and shared circulation.

Designers must also consider egress pathways and cart movement, ensuring that equipment delivery, sample transfer and emergency evacuation can occur without obstruction. Additionally, when planning circulation and workspace layout, it is essential to avoid placing fume hoods in areas of high foot traffic, as frequent movement can create air disturbances (vortices) that compromise the containment and safe operation of these critical safety devices. Importantly, space planning should anticipate not only today’s needs but also future laboratory functions, as new instruments and testing processes are introduced.

Flexibility of laboratory services: Gas, air, water and exhaust should be distributed through robust and adaptable infrastructure. Pivoting snorkel arms that rotate 360 degrees, point-of-use exhaust ports and plentiful service connections allow technicians to align the workspace with their task at hand, reducing strain while increasing efficiency. Overhead service panels equipped with quick connects for power, air, deionized water and laboratory gases create additional adaptability, enabling laboratories to reconfigure workstations without major renovations.

Looking forward, this flexibility is essential for accommodating automated laboratory equipment, which often requires larger footprints, higher clearances and expanded utility demands.

- Egress aisleway and cart circulation.

- Technician workspace ideal width: 6 feet of clearance.

- Clear line of sight from the corridor into the laboratory and between technicians within the laboratory.

- Overhead snorkel exhaust arm with 360-degree rotation to capture equipment fumes.

- Overhead service panel with quick connects for power, air, deionized water and laboratory gases.

Safety systems and emergency equipment: Modern laboratories must be equipped with comprehensive safety systems to protect occupants during hazardous events. This includes strategically located emergency showers and eyewash stations for rapid decontamination, easily accessible emergency push buttons to shut down equipment or activate alarms and clearly marked fire alarm devices throughout space.

These systems should be integrated into the laboratory’s circulation plan, ensuring unobstructed access and visibility and regularly maintained to guarantee readiness. Their placement and functionality are essential for compliance with safety codes and for supporting a culture of safety and preparedness in laboratory environments.

Smart technology integration into a laboratory’s design

While chemical safety and ergonomic design provide a necessary foundation, a third dimension — smart building technology— is reshaping how laboratories are designed, operated and maintained. By layering intelligent sensing and automation over traditional safety measures, regulatory laboratories can achieve safer, more sustainable and more resilient operations.

The primary goal of smart building technology is to make the laboratory environment safer for technicians while also increasing laboratory efficiency and improving technician quality of life.

Different types of smart systems can benefit laboratory environments, including:

- Smart lighting systems control lights and monitor light levels and motion on a by-fixture scale. This allows for complete optimization of lighting levels throughout the laboratory and accurate dimming and daylighting to ensure that electrical energy consumption for lighting is minimized. As typical occupancy/vacancy sensors are not appropriate for laboratory spaces due to potential safety hazards, smart lighting systems can ensure that no area within the laboratory is dark or powered off when the laboratory is in use while still allowing for improved energy efficiency.

- Intelligent building automation systems (BAS) can control all aspects of the heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system, including air flow, temperature and humidity and can control fume hood/extraction exhaust to create optimal conditions throughout the laboratory. These functions can also be provided by a laboratory control system (LCS), which provides an additional layer of abstraction between laboratory equipment/controls and the BAS. LCSs allow for even more functionality and specialized, lab-oriented controls.

- Real-time locating systems (RTLS) using ultra-wideband radio technology can be used to provide foot-level locations of employees and critical mobile assets throughout the facility. RTLSs on their own can provide valuable information about technician and asset paths to help develop optimized laboratory workflows.

- RTLSs can also enhance technician safety by identifying whether technicians have been stationary in a hazardous area for too long (indicating possible incapacitation) and can also provide a portable panic button for technicians to call for help in an emergency.

- Gas detection systems using internet of things or cloud-based technology allows for traditional gas detection systems to be monitored and trended online and to be interconnected with other systems, allowing for gas alerts to trigger supporting systems as needed. In addition to detecting hazardous and/or explosive gases, these systems can be used to monitor for oxygen displacement in laboratory areas to help detect nonhazardous, heavier-than-air gases that might disrupt the breathing environment.

The primary benefit of smart systems is realized when multiple smart systems are interconnected to form a single, intelligent, interconnected system. Some example integrations that can be implemented when systems are interconnected include:

- Optimized lighting controls: By interconnecting an RTLS with a smart lighting system, lighting can be further optimized to automatically activate enhanced or task lighting when technicians are using certain benches or equipment. The “dwell” time for reducing lighting levels when the space is unoccupied can also be drastically reduced by using the technician locations provided by the RTLS.

- Increased HVAC efficiency: By interconnecting an intelligent BAS with a smart lighting system and RTLS, the BAS can accurately determine — in real-time — the occupancy of each space and optimize the temperature, airflow and humidity. This also allows for near‑instant setbacks of temperature/airflow when spaces become unoccupied (if appropriate) and automatic activation of exhaust/extraction systems when spaces are occupied.

- Hands-free security and access control: By integrating an RTLS with a traditional access control system, hands-free access control can be implemented, automatically unlocking or opening doors for authorized technicians. This allows for free and interrupted flow between workspaces, increasing laboratory efficiency. By further integrating these systems with the motion detection capabilities of a smart lighting system, a security system can easily detect when unauthorized people enter spaces and alert the relevant security personnel.

- Enhanced safety during emergencies: By integrating the systems discussed previously, the safety of technicians can be greatly increased. When an emergency is detected by any of the systems (e.g., fire alarm, gas detection, security alert, technician panic alarm), the other systems can respond accordingly. For example, if a gas detector detects high gas in an area, the intelligent BAS can immediately alter the air flow in the area (exchanging additional air or sealing the area if appropriate), the smart lighting system can increase the lighting in the area and along the egress path to maximize ease of egress, the RTLS and access control systems can unlock or open doors automatically to promote rapid egress and the RTLS can provide an immediate update to managers and safety personnel regarding the location of each technician, ensuring everyone is accounted for in an emergency.

For example, if a gas detector detects high gas in an area, the intelligent BAS can immediately alter the air flow in the area (exchanging additional air or sealing the area if appropriate), the smart lighting system can increase the lighting in the area and along the egress path to maximize ease of egress, the RTLS and access control systems can unlock or open doors automatically to promote rapid egress and the RTLS can provide an immediate update to managers and safety personnel regarding the location of each technician, ensuring everyone is accounted for in an emergency.

As more smart building technologies are integrated, the benefits to productivity, efficiency and safety increase exponentially when compared to the systems operating independently.

An additional important consideration as laboratories become more advanced is the need for clean, uninterrupted power to both laboratory equipment and the smart building systems. Laboratory equipment and smart building systems depend on a clean, stable, uninterrupted supply of electrical power and are easily disrupted by even short power outages or events.

A facility level double-conversion uninterruptable power supply (UPS) can provide clean, uniform power to the entire laboratory’s lab equipment while eliminating the need to maintain multiple smaller UPSs. The double-conversion style of UPS always converts incoming power from alternating current to direct current and then back to alternating current, ensuring there are no interruptions or “blips” as the incoming power quality changes or drops in or out.

While smart building technologies can enhance laboratories, they also present significant challenges during design, construction and operation. As with all digital/computerized systems, cybersecurity and data protection is a concern. Laboratory designers should coordinate with the owner during design to establish appropriate cybersecurity controls and ensure that all systems are designed with sufficient isolation and protection to ensure laboratory safety and that data is always protected.

Additionally, as the complexity and number of integrations increases, the commissioning of the laboratory can become significantly more challenging. In some cases, a specialized contractor or commissioning agent is needed to ensure that the systems are properly integrated and all safety functions are verified before the laboratory is placed in service. Laboratory designers should evaluate the commissioning needs in cooperation with the owner during the design phase.