Specifiers and BAS developers thresh out the current state of building control technology and applications

Building-automation systems (BAS) can streamline facility management, increase energy efficiency-and give specifying engineers headaches. This month’s panel of experts sorts through the ever-churning field of building controls and offers perspective on current BAS products; the impact of Internet technology; common pitfalls; and how engineers, vendors and end users should work together to maximize BAS potential.

M/E Roundtable Participants

Steve Tom , P.E., PhD, Director of Technical Information, Automated Logic, Kennesaw, Ga.

Kim Shinn , P.E., Division Director, Tilden Lobnitz Cooper, Jacksonville, Fla.

Tom Mahrer , Lead Product Manager, Alerton Technologies, Redmond, Wash.

John Huston , P.E., Director of Technology Integration, Teng & Associates, Chicago

Kevin Osburn , Vice President, Apogee Marketing and Development, Buffalo Grove, Ill.

CSE: In your opinion, do the BAS products currently on the market have the ability to properly monitor and control buildings?

HUSTON: Better than most end users are aware. Technology advances and the ability to integrate dissimilar subsystems has resulted in efficiencies never before possible.

OSBURN: The products currently have the technical ability, but this does not automatically guarantee proper control. Many times control applications are incorrectly designed, misapplied, misunderstood or not properly commissioned.

SHINN: Also, the human side of the BAS manufacturers is often lacking in terms of expertise and ability. We have seen countless instances where the local sales staff does not understand their own product lines.

TOM: The current product generation is not perfect by any means, but does provide a pretty impressive list of functions. Take a look at any mission-critical facility today and you’ll probably find a BAS. Some have extended BAS to include manufacturing-process control because they like the power, speed and flexibility. In the future, these systems will get even better.

CSE: So what are some recent BAS innovations?

MAHRER: Open protocols, web technology, personal digital assistants (PDAs) and wireless technologies. These innovations will eventually change every aspect of a project, from design and bidding to commissioning and daily system use.

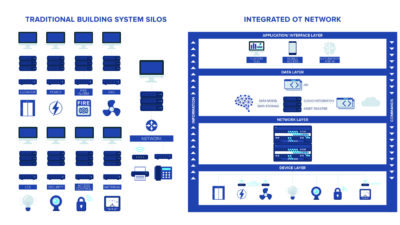

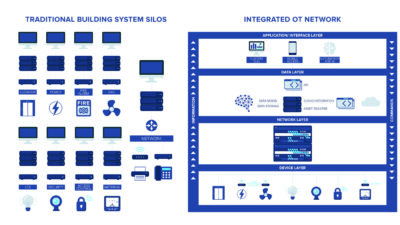

HUSTON: Open standards and technologies-like LonWorks, BACnet and MODBUS-allow control-system designers to create an infrastructure that can be built upon. The ability to integrate different subsystems enables the data sharing that increases the application base and operational efficiency.

SHINN: I think that the use of web browsers as the man-machine interface is very exciting. This puts a well-understood tool in front of building operators and helps them get the maximum functionality out of their systems.

HUSTON: Internet and wide-area network (WAN) connectivity also enables access to the BAS from anywhere, and greatly reduces software costs. Workstations no longer require expensive, proprietary software licenses. Any computer connected to the LAN or WAN can be used to access the system through a web browser, provided they have proper security clearances.

TOM: These open protocols and web-based technologies are complementary developments, even though it’s easy to mistake them for competing technologies. In the near future, I believe these developments will merge-perhaps with the BACnet committee developing an XML schema to promote interoperability.

SHINN: We are also seeing a trend to provide building occupants with more control over their personal environments. While this may sometimes result in less than optimal operating efficiency for individual building systems, the increase in labor productivity usually dwarfs the operating dollars lost. Web effects

CSE: Obviously, Internet technology has had a major impact on this industry. How, exactly, has its growth and acceptance affected BAS development?

OSBURN: Internet advancements are influencing and raising the expectations of BAS users. For example, people can already retrieve messages from anywhere in the world. Now they want to monitor and control their facilities the same way.

MAHRER: I agree. End users are accustomed to using web applications in their daily activities, so it’s influencing BAS developers to use those web interfaces for a similar look and feel. This can also reduce the training required for system operators.

SHINN: Building operators are just like the rest of us: they hate change. So as BAS systems start to use familiar Internet-based tools, it allows them to operate with a familiar technology and not be too far from their ‘comfort-zone.’

TOM: I believe that these Internet technologies are the most exciting development since direct-digital control. We have participated in several projects where we integrated multiple buildings with control systems made by multiple vendors into a single, integrated system that extended over vast geographic areas. These projects would have been impractical without the Internet.

CSE: With all of this web-based development, are facilities willing to use their existing information technology (IT) infrastructure to accommodate BAS functions?

MAHRER: Many large facilities have no choice but to use existing infrastructure, as it is cost prohibitive to rewire or add additional networks.

The most obvious danger of this arrangement is the effect on bandwidth. If done incorrectly, communication bottlenecks could be created in the existing network. Another danger is that using the Internet as a means to interface with a BAS might expose you to certain security hazards, such as hackers.

HUSTON: In reality, the system can be designed to have very little effect on bandwidth, and the security of the network can be as tight as required. All of the open ‘enterprise facility management systems’ that we have implemented to date-from high-security federal facilities to high-reliability data centers-have resided on private, secure WANs. These systems integrate third-party applications like maintenance management, inventory management, demand aggregation and as-built documentation control with the BAS. Remote access is achieved through dial-in to a server via secure authentication agent software.

OSBURN: Even though most facilities are open to this concept, some IT owners have serious reservations because design engineers and the average BAS vendor aren’t experienced in dealing with IT infrastructures. And because BAS systems are foreign to the IT professional, performance questions are difficult to answer.

Another major concern is the reliability of the BAS functions. IT staffs are accustomed to modifying and upgrading their networks during ‘off-hours.’ With BAS, there are no off-hours.

SHINN: I monitor an Internet newsgroup for operators of educational-facility physical plants, and without exception, the respondents say that IT departments are very supportive of letting BAS information share the network. The only caution came in saying that the IT staff had to be sticklers for security.

TOM: There is a lot of learning that needs to take place on both sides. IT professionals want to know more about the technical aspects of BAS, and BAS professionals need to learn a lot more about IT systems so they can answer their questions. Wireless-the future?

CSE: It has been said that wireless technology could be the future of BAS (see CSE Nov. 2001, p. 24). Do you see this being developed? Is there user demand for such products?

OSBURN: Because the electrical components of a BAS system can approach 40% of the project cost, wireless technology can attack that first cost, especially where it is difficult or expensive to run cable. There is even life-cycle cost-savings potential for areas that are remodeled frequently, because it is easier to move a wireless thermostat than one connected to a conduit.

MAHRER: But wireless technologies still face cost issues. As the price for this technology comes down, manufacturers will be able to add this to controllers, but savings on wiring and installation hasn’t quite paid for the technology just yet.

HUSTON: Wireless is being developed and playing a role at both the device level and the network level. However, we do not see a large demand for it at this time. For us, price has not been the negative issue; throughput and security have. The security concern is that if the wireless signal is available throughout a facility, it will also be available outside the facility.

When a wireless device is used, it is usually because hardwiring that device is physically impossible or cost prohibitive, so the installed cost of a wireless device is actually less.

TOM: I don’t see wired systems going away any time soon, because they have significant advantages over wireless networks.

In our own facility we have a mixture of wired and wireless networks for our entire IT structure, including the BAS. I think we’ll see a significant increase in the use of wireless in the coming years, but I wouldn’t necessarily say it’s the future of BAS. Learning from mistakes

CSE: Many building owners and specifiers have had negative experiences with BAS in the past, whether because of poor design, under performing systems or a lack of operating expertise. What has caused these problems?

OSBURN: The problems haven’t really changed since the days of pneumatic controls. I see the common ones being incorrect sizing of the mechanical system; poor BAS design or application; and buildings not being commissioned to specification.

In addition, even though building usage changes over time, we often see a lack of ongoing maintenance. People would like to think that with electronic technology they can turn it on and forget it; but this isn’t true.

MAHRER: I actually believe that the vast majority of facilities are working very well. Where there are problems, we’ve found it’s generally due to either poor maintenance-which can actually be linked to an improperly configured/underutilized BAS-or a poorly commissioned BAS.

SHINN: Quite frankly, we haven’t had many problems in the last five years. Once again, we see that the hardware is really quite good, but the personnel supporting the hardware is lacking.

HUSTON: One issue is that while the invention of microprocessor-based controllers provided a higher level of sophistication for control and monitoring, it also tied the hands of the designer because control manufacturers develop-and continue to develop-custom, proprietary solutions. So in order to obtain competitive bids, designs had to be reduced to the lowest common denominator: Mechanical engineers-not control-system designers-typically produced 25% control-system designs and performance specifications. Unfortunately, in this scenario, there are a limited number of evaluation factors and because everyone meets the spec, the lowest bid wins. But the lowest bid typically leads to low quality, in addition to change orders and claims. So the end users see poor designs, change orders, claims, under performing systems, expensive service contracts and upgrades.

TOM: A BAS can be an extraordinarily useful tool if it’s used correctly, and it’s true many of the older BAS had complex or confusing user interfaces. Operators are always ‘under the gun’ to fix problems, and if the system is confusing they will be encouraged-or forced-to bypass the BAS and manually override the system.

CSE: In general, do building owners or facility managers have the expertise to manage these systems?

OSBURN: Many times no. Not because they are not capable, but because they have not been properly trained, or do not have time to stay familiar with the technology.

SHINN: We find that the owners who invest in a BAS will make a commitment to training for maintenance. Having said that, we find that the simpler the operator interface, the more functions the owner will use and the better the system will realize its potential to save energy and provide environmental control. Simpler is almost always better.

CSE: So is the solution a more simplified control method?

MAHRER: Yes. However, more investment must also be made in training. You don’t walk up to any BAS or any building and instinctively know how to optimize its performance. Each has a set of tools and you need to know how to harvest the information and make smart decisions. Simpler is always better, and many aspects of BAS are becoming more and more streamlined- such as smart control loops that tune themselves, self-configuring controllers and preconfigured user displays.

TOM: Some functions, like adjusting setpoints or entering schedules, need to be very simple because all facility managers-regardless of expertise-will use them. More complex applications, like optimizing the control of an ice-storage system, will require a more highly trained operator. These operators need to be able to configure trends, run reports, set up alarms and perform other high-level control functions. A well-designed BAS will provide a very simple interface for day-to-day tasks, while still offering ‘power-user’ tools for advanced control functions. Open vs. closed standards

HUSTON: I maintain that it’s not the complexity of the control systems that is the problem, but the proprietary nature of the control systems and the cut-throat market.

Open standards break the proprietary lock by enabling control-system designers-not mechanical engineers-to provide 100% design of the control system based on the client’s unique requirements, while still maintaining a competitive bid environment. The most successful end users have educated themselves on the features and benefits of open controls to learn how they can be utilized. The computer industry can offer an analogy: Computers have drastically improved our lives, and although they are extremely complex, we do not try to simplify them. Instead, we create internal IT departments to support, maintain and upgrade these systems and maximize their potential. The same can be done with open-control systems: the O&M staff can become as self-supportive as required, based on each organization’s level of comfort.

CSE: What are the difficulties for design engineers or integrators when trying to specify building-control solutions?

SHINN: Unlike the laws of thermodynamics-which haven’t substantially changed in the last 800 years and form the foundation for most of HVAC design-it is all but guaranteed that we will have an entirely new set of BAS gizmos to understand every year and a half. The industry is simply moving so fast that, unless a design professional devotes significant energy to staying current, they must rely on the vendor for education and even design input.

MAHRER: Our industry is changing very fast. With new technologies, open systems and misinformation, it’s hard for system designers to be an expert on everything. These engineers really need to work closely with vendors in order to stay current.

SHINN: Unfortunately, the local salesperson frequently doesn’t have the knowledge of his own product line, much less the industry as a whole, to be of much use to us designers. Manufacturers should provide ongoing training for their own staff, so that they can truly function as consultants to the designers.

OSBURN: System designers need to be able to focus on how the building should work for the owner and then rely on the BAS vendors for advice and information on how to apply the technology. I think that our BAS industry could, and should, do a lot better with software tools that help designers specify BAS systems.

TOM: Specifying a BAS has got to be one of the toughest jobs in our industry. There is no such thing as a generic BAS because there is no such thing as a generic building or a generic customer. The specifying engineer has to carefully evaluate the building owner’s needs in terms of cost, features, interoperability, expandability and a host of other considerations. It is almost impossible to do all of this without involving BAS vendors.

BAS vendors can be very helpful in providing sample specifications, but of course those specifications will favor their system. If you’re going to sole-source the system, the vendor’s specs might be exactly what you want. If you want competitive bids, you’ll need to gather several specs and find common ground.

HUSTON: The control system should be designed by engineers that specialize in control systems, not as an ‘add-on’ to the mechanical design. Control-system technology goes far beyond mechanical systems and it needs to be continually studied and understood.

The barrier for most engineers is that the education process requires a serious commitment, with continual education, involvement and application. Teng & Associates, Inc., has had a dedicated control-system group since 1993, which has designed some of the most integrated and efficient facilities in the world.

But the vast majority of engineering firms have not made the commitment to properly design control systems, open or proprietary. Instead, they rely heavily on control-system manufacturers to provide specifications and designs. It is not the products that need to change: it is the knowledge of the end users implementing the systems and the engineers designing them.

The BAS Retrofit Challenge

Existing facilities offer a host of obstacles to the implementation of building-automation systems, as system designers are faced with integrating BAS hardware into structures, spaces and building systems that were not necessarily created with controls in mind.

Interestingly, the difficulty of the BAS design is often inversely related to the scope of the project.

‘It comes down to the degree of the retrofit,’ explains Kevin Osburn, Vice President, Apogee Marketing and Development at Siemens Building Technologies, Buffalo Grove, Ill. ‘As less and less of the building is replaced, it becomes more complex because you have to work around the existing structure, or attempt to make old HVAC equipment work like new.’

Dealing with old equipment is especially difficult, says Tom Mahrer of Alerton Technologies, Inc., when there are not original documents to work from. In addition, he notes that the labor and cost to install BAS wiring in old facilities can be incredible: ‘It is these applications that may be the first to adopt wireless [BAS] technologies.’

Another factor is the complexity of integrating existing control functions. This could involve both the incompatibility between proprietary systems and the challenge of migrating to a system based on open protocols.

‘The biggest challenge that we face is the owner’s desire to move to an open system platform, but continue to support-and in some cases integrate with-an existing, proprietary ‘legacy’ BAS,’ confirms Kim Shinn, P.E., Tilden Lobnitz Cooper, Jacksonville, Fla.

Teng & Associates, Chicago, has a special control-system team that specializes in just such projects. Their director of technology integration, John Huston, P.E., has applied BAS in a number of facilities (See ‘Mission: Intelligence,’ CSE February 1999). According to him, there is no definite method for these projects, as every building is unique.

‘The challenges faced are related to addressing the many unique circumstances and requirements of each facility,’ he asserts.

And as Steve Tom, P.E., of Automated Logic reminds us, it is important to remember that when attempting to improve building-system efficiencies, BAS is no panacea.

‘It’s important to take a look at the overall design to make certain the mechanical systems are still appropriate for the current operation. Sometimes there’s been a change in occupancy or a change in function that makes the entire mechanical system ill-suited for the new use. If that’s the case, a new control system is not going to solve the problem, even if it is a BAS.’

To read about BAS retrofit projects undertaken by our panel of experts, visit the ‘Deep Links’ at