Commissioning has been a formally recognized practice in project delivery for about a decade. ASHRAE defines commissioning as “a quality-focusedprocess for enhancing the delivery of a project. The process focuses on verifying and documenting that the facility and all of its systems and assemblies are planned, designed, installed, tested, operated and maintained to meet the Owner’s ...

Commissioning has been a formally recognized practice in project delivery for about a decade. ASHRAE defines commissioning as “a quality-focusedprocess for enhancing the delivery of a project. The process focuses on verifying and documenting that the facility and all of its systems and assemblies are planned, designed, installed, tested, operated and maintained to meet the Owner’s Project Requirements.” And this, ultimately, is what all commissioning providers are shooting for.

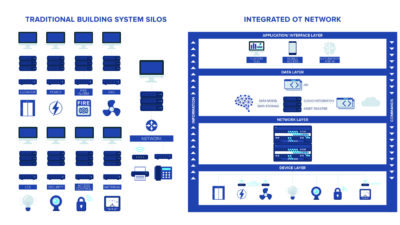

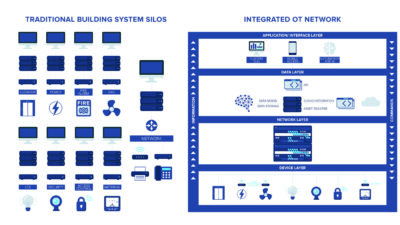

Commissioning of the building automation system (BAS) early is critical, because it is then used to commission other systems. Our experience over the past eight years with commissioning services related to BAS has consistently demonstrated one significant issue: There are far too often critical deficiencies in the implementation of the design intent articulated by the project team in the installation and startup of the systems on site. These relate principally to the following issues:

• The controls subcontractor is the last installer in the overall sequence of trades on projects, and frequently lags the completion of other installed systems. The controls system is not functioning or barely operating when the commissioning agent is scheduled to carry out functional performance verification testing on HVAC and supplementary systems.

As a result, we wait for the controls installation to be completed, or the sequences of operations cannot be verified because the controls system fails to perform all of the interfaces— those internal to the BAS and the interfaces with the systems that BAS monitors.

• The composite controls/automation system is a patchwork of standard modules marketed by the manufacturer, and the combination of these elements does not specifically comply with the design intent.

• Record documentation—all submittals, RFIs/responses/resolution, as-built drawings, operation and maintenance manuals and videotapes (or other media records) of training sessions—is detailed as it relates to individual components within the installation, but there often is minimal or no description of the sequences of operation or how to diagnose problems when the sequences do not perform as intended.

• Providing accurate component identification (tagging) within the systems as required by the plans and specifications has also become problematic during the functional testing phase of the commissioning process.

• Training of building system operators by subcontractors usually consists of highlighting the technical attributes of the installed components. This is not training, because it does not address the real needs of the personnel who are charged with the responsibility of efficiently operating and maintaining the systems over the life cycle of the facility.

Because commissioning is a relatively new industry, at least in the formal nature of the rigorous functional performance verification testing that is the focus of the process, BAS manufacturers and installers are finding that a high level of third-party scrutiny is now being given to the sequences of operation, transition of system functioning as seasons and outside weather changes and the interfaces among systems.

In order to avoid the potential that numerous functional tests receive fail results, when appropriately implemented, commissioning should incorporate the following requirements:

• Soon after construction contracts have been awarded, commissioning providers should meet with the construction manager or general contractor to integrate the commissioning activities into the master construction schedule. Because the commissioning agent wants to start functional performance verification testing as early as possible, they collaborate with the contractors to schedule equipment startup and completion of systems, or portions of systems, to allow testing to proceed. In some instances, this fast-tracking of functional testing will require subcontractors to revise the sequence of component and system installation. The importance of scheduling the controls subcontractor to advance work to meet this sequence is clear and must be communicated early. This approach marks a significant change from the traditional situation and has met with resistance, on occasion, from controls installers.

• During the submittal process, along with the design engineer, commissioning providers determine how closely the control configuration satisfies the design intent. It is not just a question of the temperature sensors and damper-control devices meeting the specification. The more critical issue is system capability to perform all of the designated HVAC sequences of operation and interface points with other operating elements, and integrate with other building systems without having to implement unique fixes as supplementary to the scope of submitted packages. This requires detailed and close cooperation between the design engineer and commissioning provider who are reviewing the submittals. It is critical to identify deficiencies at this stage, before installation of the control system commences.

• Not more than 60 to 90 days following submittal approval, the commissioning provider requests the first draft of operating and maintenance manuals from the contractors. The timing is important, because the sequence of draft review and revisions always drags out. Commissioning providers should have the final, approved manuals available to the operating personnel a minimum 60 days before training sessions commence.

Similar to all issues described in this presentation, the quality of information prevails. It is important that the operation and maintenance material submitted contain the information of the components that are currently installed and not be generic. Operating personnel will want sequence of operation details and troubleshooting explanations in the manuals. While parts lists and specification criteria for components are useful, this is not the information that will help the operating personnel when the chilled-water system unexpectedly shuts down and initial re-start procedures are not working.

How the information is organized also is important, because the operating personnel must be able to locate specific information in a short time. When feasible, owners should negotiate significant contract allowances in the schedule of values related to submission of operating and maintenance information, as this has frequently remained an issue beyond substantial completion. We have assisted owners by compiling the requisite operating and maintenance manuals when subcontractors have failed to deliver this essential information, in order to provide the operating personnel with pre-training help.

• Training of building operating personnel is a key element to the successful long-term asset management of any facility. The contract specifications must clearly outline the extent of training, technical qualifications of trainers, flexibility of scheduling the training sessions and evaluation procedures to ensure that the training program is successful. While the training of operating personnel related to various building systems is a high priority, training associated with the control/automation system must be given the highestpriority.

We typically request that building operating personnel accompany us as we supervise functional performance tests, because we believe that this is an additional training opportunity and gives the personnel “hands on” exposure to the various sequences of operation as the contractors are demonstrating these for our performance assessment.

This article discusses some of the issues that we believe are important in the commissioning process associated with control/automation systems. It must be emphasized that these apply to the process for implementing commissioning, and there exists a parallel consideration of scope, which we have not addressed. For example, should the functional performance testing apply to all of the control points or is a sampling strategy sufficiently adequate to determine performance compliance with the design intent and contract specifications? If so, what is an appropriate level of sampling to reflect the performance requirements?