Buildings all over the country, constructed in the '50s, '60s and '70s "need massive upgrading," declares Bill Helmuth, AIA, design director for the Washington, D.C. office of A/E HOK. In the private sector this is not welcome news, as buildings from these eras aren't exactly retrofit-friendly because of narrow floor plates and low floor-to-floor heights.

Buildings all over the country, constructed in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s “need massive upgrading,” declares Bill Helmuth, AIA, design director for the Washington, D.C. office of A/E HOK. In the private sector this is not welcome news, as buildings from these eras aren’t exactly retrofit-friendly because of narrow floor plates and low floor-to-floor heights. As a result, owners and developers tend to shy away from such work. For the U.S. government this is not an option. Not only does the government own a significant amount of property, it also has an interest in preserving its buildings for their historic value.

Of course, preserving classic facades, lobbies and even valuable artwork while simultaneously building an infrastructure to support a modern-day, high-tech environment is no simple undertaking. “Value judgments must be made; there may be a conflict of interest between present goals, programming goals or even code requirements,” explains Joe Wells, AIA, senior vice president with the D.C. office of HSMM.

“Retrofits can be challenging mainly for the unknown,” adds Keith O’Higgins, P.E., president, Metro Design, Schaumburg, Ill. “Since there are no drawings available, you don’t know what’s behind the walls—for example, whether you might be dealing with something like asbestos or other hazardous materials.”

The other major difficulty is “shoehorning” today’s systems into yesterday’s buildings.

Budgets, adds Helmuth, must also include sufficient funds to upgrade these old buildings’ skins if true energy efficiency is to be achieved.

Another important trend, adds Dave Thompson, AIA, a vice president with RTKL’s Washington, D.C. office., is designing for space efficiency and flexibility—not just from a standpoint of accommodating future technology, but for savings in the short run. “The government is having to make do with less and to make facilities go further,” he says. “This means packing people in tighter and going without luxuries. This is the trend with the bulk of federal work, although there are still a few premier projects.”

But there are solutions, according to Frank J. Becker, P.E., senior principal, GHT Limited, Arlington, Va. “You’ve got to get outside the box,” he claims.

For example, Becker points out that many older buildings have high window sills, which can bring in the sunlight. Cutting in light wells that can harvest daylight from the roof and then be piped throughout a building via atriums, mirrors or even fiber optics, is one such solution.

The key to addressing these challenges, Wells believes, is a multidisciplinary team. “This often requires a large team effort and a lot of communication between all of the disciplines involved in the project,” he says.

Ensuring security

Besides budgetary constraints, the real world is also coming to bear on retrofit work in the form of heightened security. A particular challenge is maintaining security during construction—and often during operations as well—when other parts of the facility are still occupied. “Security during construction can have a significant cost impact and needs to be in the original contract so that it can be accounted for in the budget,” cautions Wells.

As far as actual measures, Barbara Myerchin, P.E., manager of the Washington, D.C. office of Affiliated Engineers, explains that the government, for the most part, isn’t installing the most cutting-edge technologies in these retrofits, but it is keeping a close eye on them. For example, she says the government is seriously looking at how anti-bioterrorism devices are developing by specifically addressing previous problems with both false positives and false negatives. “They’re looking at more sophistication filtration systems, as well as chemical and biological detectors on the market, to see whether or not they are viable,” says Myerchin. “I think we’ll soon see agencies such as GSA installing these and connecting them to the air-handling system.”

The installation of chemical, biological and radiological detectors may soon follow, depending upon the results of further applied research—something slightly frustrating from Well’s perspective. “New standards are coming out and we’re testing the effectiveness of certain security measures. But what we did three months ago may be totally different today because there are so many evaluation and testing efforts underway,” he says.

The impact of security, he adds, is a great example of how critical it is for A/Es to better understand an existing building and its operations prior to designing. For example, the phasing of work in an occupied building can impact the actual design.

“More communication is needed so that the occupants understand what they’re going to be living with on a week-to-week basis as far as noise, dust and the containment of hazardous materials, for example,” says Thompson.

Phased renovations also tend to extend project schedules. And the extent to which security measures must be taken will vary according to the project, as well as location. “Security during renovations will be easier on campus, but more difficult in a downtown setting,” says Myerchin.

But a critical element designers cannot lose sight of, stresses Charles Hahl, P.E., president, the Protection Engineering Group, Chantilly, Va., is losing the elegance and beauty of these classic buildings. Unfortunately, many lobbies are jammed with security hardware, and frankly, the processing of visitors is often not so graceful.

“But they’re trying to plan it better and make it look better,” says Hahl.

This concern is partially motivated by the GSA’s First Impression program, adds Hellmuth, which places a value on the public’s perception of a building. In turn, funding is earmarked to address this issue.

Sprinkler simplicity

Reversing the trend toward more technological solutions, Hahl notes, traditional life-safety measures are becoming more common. “They’re choosing more traditional sprinkler systems in lieu of special clean agents or pipe suppression systems.”

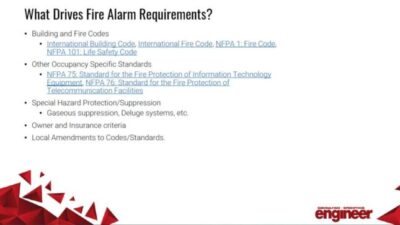

The bottom line, he says, is that simplified operations and maintenance are more cost effective in the long run. That said, significant changes are occurring in the realm of mass notification systems. In fact, the Dept. of Defense recently mandated the incorporation of these systems. But even in non-DoD facilities, the trend has been to install voice-type fire-alarm systems with mass notification capabilities, whereas in the past, such devices would only be found in high-rises or assembly facilities, says Hahl.

The public client

Of course, working with government is an experience in and of itself. For example, Hahl says GSA is now choosing the most current model building codes available for just about all of its projects. Indeed, the government, as a whole, has it’s own set of criteria. As a result, Thompson claims, “The design effort isn’t always so efficient, as little things are required all throughout the process that you don’t have in the private sector.”

Wells adds that with A/Es on staff at government agencies, the review process is more populated and, naturally, slowed down.

For these reasons, O’Higgins shies away from federal projects. “I think that the public sector is much more arduous from a standpoint of what it takes to get a project from conception to completion. On a local level, you still have that, but you’re not dealing with bureaucrats miles and miles away.” Becker, on the other hand, is more at ease with the status quo. “You follow the bureaucracy to get the brass ring,” he says. “Is it better? Sometimes. Is it worse? Sometimes.”

John Shimm, AIA, principal, Burt Hill Kosar Rittelmann, Pittsburgh, also admits that it’s a more involved process, but he’ll take government clients any day. “They’re a great client. They understand value and they’re committed to their mission,” he says. “Projects may be long and drawn out, but they have a good methodology with attention to value and cost.”

Design-build enters the picture

That said, one methodology the government has turned to is design-build.

“For the Dept. of Defense, design-build is the fastest growing delivery method for small to average projects,” says Wells.

The advantages? Speedier delivery time, less budget overrun and fewer change orders.

The State Dept. is also utilizing it for most of their large projects. Other government agencies, like the GSA, he adds, are using it occasionally, viewing design-build as a “tool in their toolbox.”

Conversely, the Dept. of Health and Human Services, according to Mycherin, recently decided to go with design-build on all its projects unless it can be proven that another delivery method would be better.

“Now we have to submit a fee before we’re even selected,” she says. “It’s a major shift and this can be very difficult on technically complex projects.”

How about new construction?

Design-build, of course tends to be better suited for new construction and the federal government is doing plenty of it. What’s going on in 2005? The State Dept., according to Wells, is planning to spend $6 billion to upgrade and build a number of new embassies. In addition, the Dept. of Defense is funding a couple of large military intelligence projects, as well as investing in border protection and guarding against bio-terrorism threats.

Also on the military front, base realignments continue to be a consistent source of work, not to mention the fact that there’s been a focus on making the military more attractive as a career, according to Mark Hebden, AIA, a vice president with Philadelphia-based EwingCole’s government practice. This has meant enlisting the help of A/E designers to improve housing, medical, training and even recreational facilities to make them more comfortable for military personnel and their families.

“Also, wherever troops are being deployed, this creates a need for new facilities,” he adds.

Crystal ball says…

Outside DoD and the State Dept., however, while much of the federal government’s plans for new construction have been deferred, the good news is that GSA continues to implement its life-cycle renovations program for older buildings.

For example, the one-million-sq.-ft. Cohen Building in Washington, D.C. had new fire-protection systems installed within and is now home to the Dept. of Health and Human Services and the Voice of America, among other federal agencies.

Similarly, the National Institute of Health, also in D.C., is currently having its 257,000 sq. ft. of space, which is spread over six floors, renovated to serve as a lab building for the National Cancer Institute.

On the other hand, Hebden points to 2006 budget reductions as a sign that things may not be so robust in the coming year. That is, unless Congress steps in and makes some budgetary changes.

Others, like Hahl, don’t see things accelerating significantly, but rather, remaining about the same.

But Hellmuth points out that’s just the nature of government work. It’s almost never boom or bust, but in his assessment, there is a pent-up demand for improving the workplace of the government employee.

“I think we’re going to see a good amount of renovation coming along … building quietly, but steadily.”

War in Iraq Impacting Work

Renovations and restorations are a significant percentage of U.S. General Service Administration projects nationwide, and are making up a good portion of the public sector work on design firm dockets. At the same time, however, A/Es report that the overall government market appears to have slowed somewhat.

“For both new and retrofit [government work], the last year has been down,” notes Dave Thompson, AIA, a vice president with RTKL’s Washington, D.C. office. “There’s no doubt that tax dollars are going to the war effort in Iraq,” he says.

Thompson adds that even though there’s been a lot of publicity on a few large projects, “they have been painfully slow in getting started.”

Joe Wells, AIA, senior vice president, HSMM, Washington, D.C., offers a cheerier view. He claims that the government’s budget for building projects has, in fact, remained steady. Yet, Wells also admits that the market is nowhere as active as it once was. It may well, in part, be due to the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Things slowed down significantly, as the government took a step back, trying to figure out how to proceed, explains Frank J. Becker, P.E., senior principal, GHT Limited, Arlington, Va.

“It took a while for balance to come back into the design process, and many projects fell behind schedule. Now these projects are getting back into the queue,” he reasons. “So it may look like the government is doing a lot of work, but if you take a look at the curve for the past five to 10 years, you’ll see that the work now is making up for the dip.”