The old adage "time is money" is truer than ever. So much so that a quality assurance solution that both ensures efficiency and preserves efficacy is the holy grail of the building industry. But just as many of King Arthur's knights failed to see the grail before them, so do engineers not see the solution before their eyes: commissioning.

The old adage “time is money” is truer than ever. So much so that a quality assurance solution that both ensures efficiency and preserves efficacy is the holy grail of the building industry. But just as many of King Arthur’s knights failed to see the grail before them, so do engineers not see the solution before their eyes: commissioning. The often-misunderstood practice of commissioning is just such a process that ensures all building systems perform interactively and according to the owner’s operational needs and the design intent.

Unfortunately, owners and facility managers often see it as merely an added cost for services they think they’re already getting. But it would be a mistake to forgo commissioning, and here’s why:

The commissioning process can accelerate the systems development of a project by years, because the commissioning agent can immediately ferret out kinks and discrepancies between multiple systems, flaws that individual, highly specialized contractors aren’t looking for.

But commissioning is more than an “insurance policy.” Full-blown commissioning serves to verify and calibrate the integration of building systems; maximizes energy conservation at a system level; prepares operations and maintenance (O&M) documentation; and educates facilities management personnel for a smooth-running building. Executed correctly, the process can harmonize all systems and verifies that they’re integrated.

For instance, in an existing seven-building office complex in Portland, Ore., commissioning revealed that a small problem was wasting considerable power: a faulty relay kept the reheat system on all the time. The building felt comfortable, but the system was wasting energy. By correcting it, the owner saved 1.4 million kWh per year with a $19,000 investment. The payback was less than one year.

Going beyond “Does the building work?”

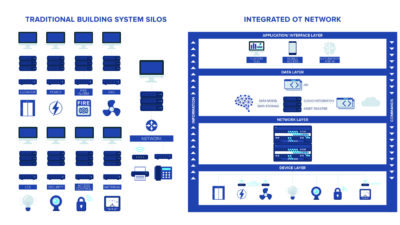

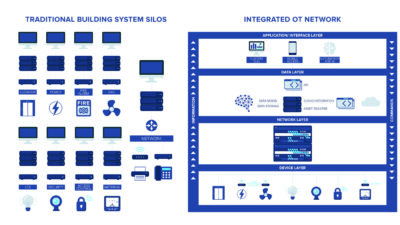

As technologies become more sophisticated, the engineered systems increasingly operate in concert with one another. It is imperative that the construction process facilitate effective integration among multiple trades at the installation phase. Commissioning agents are often the team members promoting this integration.

Generally, the role of commissioning agents has been perceived as verifying that the design intent related to HVAC, electrical, plumbing and security systems is met by construction specialties. In other words, by testing and assuring that both the building equipment and the building systems work well together, commissioning answers the question, “Does the building work?”

Before the advent of building commissioning, the U.S. General Services Administration provided public sector clients with verification that each piece of equipment accepted at the jobsite was, indeed, the model number ordered. Commissioning was borne of this process.

But today’s commissioning process has moved far beyond simple equipment verification, to the testing of complete installation of equipment components related to the systems. Many times, this testing is part of the process verifying that the site has undergone full preparation for the commissioning activities, also known as the “pre-function checklist.”

Subsequent to insuring that each item on the pre-function checklist is present and connected, the commissioning authority exercises the equipment—and associated systems—through a variety of design capacity sequences to verify that mechanical components, electrical/mechanical connections, controls devices, building management interfaces and other related components are calibrated, set, marked, operating and capable of producing the desired results as specified by design intent.

Maximizing energy conservation

Commissioning, however, shouldn’t be limited to testing and verifying that integrated systems satisfy design intent. Another vital function should be to maximize energy-conservation strategies through the optimal balancing of systems and cross-integration of related systems.

Equipment can function and entire systems can operate within a wide range of settings. And substantial life-cycle cost savings can be realized by optimal balancing, calibrating and integrating of major building systems.

This is an aspect that for building owners has grown dramatically in importance with increasing volatility of energy prices. The desire to rein in unnecessary costs is fueling a new industry niche: retro-commissioning, which focuses on existing buildings.

For example, for its Capitol Building, with 600,000 sq.ft., the state of Texas invested $200,000 in a retro-commissioning effort and realized increased occupant comfort and enough energy savings to support a 1 1/2-year payback. According to the National Association of State Energy Officials, the building realized electricity, heating and cooling savings of $144,700 per year, or 27% of its previous annual energy costs.

Getting facility managers involved

An often overlooked concern, but one that is essential to maintaining systems harmony after the facility has been handed over to the owner, is the involvement of the facilities team in the commissioning process. Even systems based on “good design practice” can fail once facilities personnel take command of the building. For example, to satisfy immediate demands of end users, facility staff might reset systems or operate them in a manner inconsistent with the original design. The building may still “work,” but in the long run, it won’t serve the users well, not to mention the toll on energy resource management.

Facilities personnel are typically provided with a final commissioning report at the end of the commissioning process. The preparation of documents and commissioning logs, and the participation of building maintenance personnel in the testing and commissioning process, provides a valuable knowledge exchange between the building’s design and operations participants.

Wayne Dunn, of Sunbelt Engineering, Jacksonville, Fla., indicates that commissioning efforts at the state of Florida’s Capital Circle Office Complex reduced energy consumption, identified equipment operating in unstable conditions and allowed for operational improvements that increased occupant comfort at minimal cost. But, Dunn points out, the commissioning documentation is “perhaps just as important for long-term savings, in that we leave a baseline of data for future operations personnel. The savings can be monitored and maintained.”

All of the pre-functional checklists, functional checklists and other commissioning record documentation become a part of this final commissioning report for the users.

Getting commissioners involved

In order to optimize the commissioning process, it is critical that maintenance personnel are also involved in the process and present during the testing procedures. A neatly bound text does little good without a thorough understanding of the design intent, system relationships and optimized set-points.

But by necessity, any building project is separated into distinct phases. The involvement of a commissioning team in each of these phases can dramatically increase long-term operation and, as a result, client satisfaction.

Guidelines for Integrated Systems

In August 2002 ASHRAE opened a guideline for public review—Guideline OP, The Commissioning Process . Once it is approved, the guideline will also be used by the National Institute of Building Sciences as its Total Building Commissioning Process Guideline. Once approved, the new guideline will supercede the existing ASHRAE Guideline 1-1996 (pictured).

“Using this integrated process results in owners receiving the expected, including a fully functional, fine-tuned facility,” says Charles Dorgan, Ph.D., P.E., chair of the committee that is writing the guideline. “It ensures complete documentation of systems and assemblies—and trained operating and maintenance personnel.”

With increasing interdependence and integration of systems, explains Dorgan, a deficiency in one system can result in less than optimal performance by other systems. The intent of the guideline is to provide a quality delivery process that assists in carrying the owner’s project requirements from pre-design through one or more years of occupancy.

In fact, the objectives in creating Guideline OP are very much focused on the owner, not only in clearly documenting an owner’s project requirements, but also in verifying that operation and maintenance personnel are properly trained.

For more information, visit the web at: